Diverse Classrooms

What separates a first philosophy course from, say, a first calculus or organic chemistry course is that students in a philosophy course have already thought quite a bit about the subject matter before they even begin their formal studies. They've wrestled with questions about their moral obligations to friends and strangers. They've wrestled with systems that seem unjust. They've been steeped in the moral and religious culture of their families, communities, and countries. And they've already made some hard decisions about what will make them happy. We are all philosophical animals, and by the time someone has arrived at a university, they've had many years to gather evidence about the major questions raised in a PWOL course.

Teaching practices and curriculum design help students to turn these informal philosophical tendencies into more rigorous and satisfying intellectual habits, while also giving students space and tools to question received views. Most importantly, these courses should leverage the wealth of personal and cultural knowledge that students from diverse backgrounds bring to philosophical debates.

Our Network draws from many different types of philosophy programs -- from large public universities to small liberal arts colleges; from women's colleges to HBCUs to schools affiliated with various religious traditions; from North America to Europe to Singapore and Shanghai. Diversity (in students, faculty, methods, institutions) is an asset in any Way of Life course, and the Network is committed to building curricula and teaching practices that reflect this.

There are three specific ways that a PWOL course can interplay with classroom diversity:

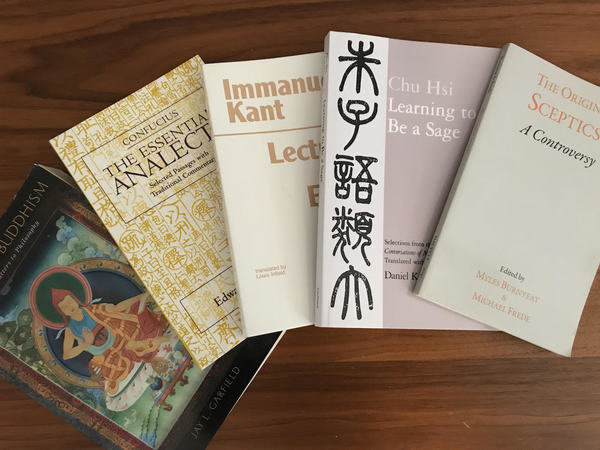

Texts we have offered masterclasses on.

Texts we have offered masterclasses on.

A Naturally Global Canon: In 300-500 BC, philosophy took root in four different world cultures. In China during the Zhou Dynasty, Confucius was synthesizing and systematizing virtue ethics. In India, Siddhartha Gautama taught metaphysical theories and ethical practices aimed at enlightenment. In the Middle East, the authors of the Wisdom literature were raising questions about the nature of faith, the origin of suffering and the challenges of leading a meaningful life -- insights that would inform the philosophical basis for each of the major Abrahamic religions. And in Greece, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle were devising methods and theories that would come to be the cornerstone of Western approaches to thinking about the good.

These ancient source texts for PWOL courses invite us to think about how these cultures interact, converge and diverge. And PWOL courses can and should be built around texts that help students discover the philosophical arguments and practices that shaped the world they now encounter. In the Resources page, we are building an extensive, searchable database of potential texts and topics for building your course. For many instructors, teaching these texts requires stepping outside areas of research expertise or comfort. With the Mellon PWOL Network, we are also building a support system of faculty and resources to help you expand your teaching repertoire in a deep and responsible way. This includes masterclasses at our summer workshops, as well as more informal connections that enable you to ask questions about texts and traditions that may be new to you.

Respect for the Knowledge Students Bring to PWOL Courses: Another, equally important concept behind good course design is knowing the particular students the course will serve and the backgrounds they are likely to bring to their philosophical investigations. In our summer conferences, we hold workshops on how to build more inclusive class discussions and engage the views of students from communities traditionally underrepresented in academic philosophy. Many PWOL courses also feature immersive assignments with learning goals designed to help students examine the philosophical evidence that comes from their lived experience.

A Systematic Approach to Dialogue: Finally, it takes skill from both the instructor and the students to be able to translate this kind of evidence into rigorous philosophical thinking. One early skill that many PWOL courses focus on is the art of dialogue -- asking strong questions, creating environments where difficult topics can be discussed authentically, and cultivating the ability to change one's mind in response to better evidence. These skills are not only essential to good philosophy, they help students become friends, neighbors, managers, and citizens who are equipped with intellectual and interpersonal skills for operating in a diverse world.

"Kierkegaard described the Hegelian system as a grand palace set up by someone who then lived in a hovel or at best in the porter's lodge. A moral philosophy should be inhabited." -Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good.