What God Would Allow So Much Suffering?

The Problem of Evil

"Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then where does evil come from?"

|

This succinct statement of the Problem of Evil is from the Enlightenment-era philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), but the problem can be traced back to ancient times. It centers around the apparent contradiction between the existence of a benevolent, all-powerful God and the existence of suffering in the world. Here is a formulation of the Problem of Evil as a philosophical argument:

Conclusion: God does not exist. Note that the Problem of Evil does not disprove all gods, only an all-powerful and all-good god like the one in Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The existence of unnecessary suffering does not challenge belief in a god that is limited in power, knowledge, or goodness, since a more limited god could be ignorant of this suffering, or could be unable or unwilling to prevent it. |

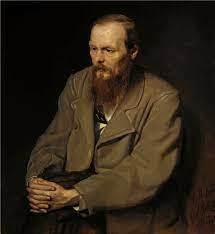

Introduction to Dostoevsky

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) was a Russian novelist, journalist, and philosopher whose work explores the political, social, and spiritual dimensions of human psychology. He is considered one of the greatest psychological novelists and began the genre of existentialist literature. Major themes of his work focus on the dark aspects of human nature, attempting to understand the pathological states behind evil actions and individuals. He was influenced by prominent philosophical and literary figures like St. Augustine, Plato, Immanuel Kant, William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Edgar Allen Poe, and many others. He was also a major influence on later philosophers in the existentialist tradition, such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre. One particular work by Dostoevsky is The Brothers Karamazov, which explores major theological and philosophical themes, such as the origin of evil, the nature of freedom, and humanity's craving for faith, through the lives of four sons of a neglectful father. Here, we will examine Book V, Chapter IV of The Brothers Karamazov, entitled "Rebellion". The chapter concerns a dialogue between Ivan – the intellectual, rational skeptic brother – and Aloysha – the brother who embodies pure and innocent Christian faith. Ivan challenges people’s love of God due to the endless and unnecessary suffering in the world, something that makes the paradise religion promises after death meaningless. In short, Ivan is describing the Problem of Evil. |

The Suffering of Children

Why Children?

|

Ivan focuses his Problem of Evil argument on three stories of children suffering, not because they are the only ones for which the argument applies, but because they are the most obvious and poignant case of innocents suffering. While normally calm and rational, in these passages Ivan is manic, beside himself, and scattered. He seems like he has been holding in his pity and rage for so long and it is all bursting out at this moment. |

"You asked just now what I was driving at. You see, I am fond of collecting certain facts, and, would you believe, I even copy anecdotes of a certain sort from newspapers and books, and I've already got a fine collection…"

Richard the Reformed Murderer

| Ivan begins with the story of a man who was severely neglected as a child, grew up to be a murderer, and was reformed in prison and ‘redeemed.’ Ivan uses this story to demonstrate that, even if the person committing the evil sees the error of their ways later and repents, the damage is already done, and no amount of punishment or repentance can ever change that. |

“I have a charming pamphlet, translated from the French, describing how, quite recently, five years ago, a murderer, Richard, was executed—a young man, I believe, of three and twenty, who repented and was converted to the Christian faith at the very scaffold. This Richard was an illegitimate child who was given as a child of six by his parents to some shepherds on the Swiss mountains. They brought him up to work for them. He grew up like a little wild beast among them. The shepherds taught him nothing, and scarcely fed or clothed him, but sent him out at seven to herd the flock in cold and wet, and no one hesitated or scrupled to treat him so. Quite the contrary, they thought they had every right, for Richard had been given to them as a chattel, and they did not even see the necessity of feeding him. Richard himself describes how in those years, like the Prodigal Son in the Gospel, he longed to eat of the mash given to the pigs, which were fattened for sale. But they wouldn't even give him that, and beat him when he stole from the pigs. And that was how he spent all his childhood and his youth, till he grew up and was strong enough to go away and be a thief. The savage began to earn his living as a day laborer in Geneva. He drank what he earned, he lived like a brute, and finished by killing and robbing an old man. He was caught, tried, and condemned to death.

“And in prison he was immediately surrounded by pastors, members of Christian brotherhoods, philanthropic ladies, and the like. They taught him to read and write in prison, and expounded the Gospel to him. They exhorted him, worked upon him, drummed at him incessantly, till at last he solemnly confessed his crime. He was converted. He wrote to the court himself that he was a monster, but that in the end God had vouchsafed him light and shown grace. All Geneva was in excitement about him— all philanthropic and religious Geneva. All the aristocratic and well-bred society of the town rushed to the prison, kissed Richard and embraced him; ‘You are our brother, you have found grace.’ And Richard does nothing but weep with emotion, ‘Yes, I've found grace! All my youth and childhood I was glad of pigs' food, but now even I have found grace. I am dying in the Lord.’ ‘Yes, Richard, die in the Lord; you have shed blood and must die. Though it's not your fault that you knew not the Lord, when you coveted the pigs' food and were beaten for stealing it (which was very wrong of you, for stealing is forbidden); but you've shed blood and you must die.’ And on the last day, Richard, perfectly limp, did nothing but cry and repeat every minute: ‘This is my happiest day. I am going to the Lord.’ ‘Yes,’ cry the pastors and the judges and philanthropic ladies. ‘This is the happiest day of your life, for you are going to the Lord!’ They all walk or drive to the scaffold in procession behind the prison van. At the scaffold they call to Richard: ‘Die, brother, die in the Lord, for even thou hast found grace!’ And so, covered with his brothers' kisses, Richard is dragged on to the scaffold, and led to the guillotine. And they chopped off his head in brotherly fashion, because he had found grace.“

The Beaten Daughter

| Ivan then recounts the abuse experienced by a daughter at the hands of her parents. The parents are praised for their actions, as it seemingly produced a well-rounded child. Here, Ivan is arguing that the girl, innocent and not susceptible to sin, was dealt unnecessary suffering no afterlife can compensate for. He condemns the Creator for such a world where children are punished but adults, the true sinners, are lauded. Why is this suffering necessary? What does this say about an all-powerful and all-good God? |

“A well-educated, cultured gentleman and his wife beat their own child with a birch-rod, a girl of seven. I have an exact account of it. The papa was glad that the birch was covered with twigs. ‘It stings more,’ said he, and so he began stinging his daughter. I know for a fact there are people who at every blow are worked up to sensuality, to literal sensuality, which increases progressively at every blow they inflict. They beat for a minute, for five minutes, for ten minutes, more often and more savagely. The child screams. At last the child cannot scream, it gasps, ‘Daddy! daddy!’

“By some diabolical unseemly chance the case was brought into court. A counsel is engaged. The Russian people have long called a barrister ‘a conscience for hire.’ The counsel protests in his client's defense. ‘It's such a simple thing,’ he says, ‘an everyday domestic event. A father corrects his child. To our shame be it said, it is brought into court.’ The jury, convinced by him, give a favorable verdict. The public roars with delight that the torturer is acquitted. Ah, pity I wasn't there! I would have proposed to raise a subscription in his honor! Charming pictures.

“But I've still better things about children. I've collected a great, great deal about Russian children, Alyosha. There was a little girl of five who was hated by her father and mother, ‘most worthy and respectable people, of good education and breeding.’ You see, I must repeat again, it is a peculiar characteristic of many people, this love of torturing children, and children only. To all other types of humanity these torturers behave mildly and benevolently, like cultivated and humane Europeans; but they are very fond of tormenting children, even fond of children themselves in that sense. It's just their defenselessness that tempts the tormentor, just the angelic confidence of the child who has no refuge and no appeal, that sets his vile blood on fire. In every man, of course, a demon lies hidden—the demon of rage, the demon of lustful heat at the screams of the tortured victim, the demon of lawlessness let off the chain, the demon of diseases that follow on vice, gout, kidney disease, and so on.

“This poor child of five was subjected to every possible torture by those cultivated parents. They beat her, thrashed her, kicked her for no reason till her body was one bruise. Then, they went to greater refinements of cruelty—shut her up all night in the cold and frost in a privy, and because she didn't ask to be taken up at night (as though a child of five sleeping its angelic, sound sleep could be trained to wake and ask), they smeared her face and filled her mouth with excrement, and it was her mother, her mother did this. And that mother could sleep, hearing the poor child's groans!

“Can you understand why a little creature, who can't even understand what's done to her, should beat her little aching heart with her tiny fist in the dark and the cold, and weep her meek unresentful tears to dear, kind God to protect her? Do you understand that, friend and brother, you pious and humble novice? Do you understand why this infamy must be and is permitted? Without it, I am told, man could not have existed on earth, for he could not have known good and evil. Why should he know that diabolical good and evil when it costs so much? Why, the whole world of knowledge is not worth that child's prayer to ‘dear, kind God’! I say nothing of the sufferings of grown-up people, they have eaten the apple, damn them, and the devil take them all! But these little ones! I am making you suffer, Alyosha, you are not yourself. I'll leave off if you like.“

The General and the Boy

|

Perhaps you’re feeling as pained as Alyosha at this point. But Ivan is not done. In response to Ivan's question about stopping, Alyosha mutters "Never mind. I want to suffer too." Faced with the suffering of the world, he wants to suffer too, as if his own suffering can somehow serve as a remedy. |

“Never mind. I want to suffer too,” muttered Alyosha.

“One picture, only one more, because it's so curious, so characteristic, and I have only just read it in some collection of Russian antiquities. I've forgotten the name. I must look it up. It was in the darkest days of serfdom at the beginning of the century, and long live the Liberator of the People! There was in those days a general of aristocratic connections, the owner of great estates, one of those men—somewhat exceptional, I believe, even then—who, retiring from the service into a life of leisure, are convinced that they've earned absolute power over the lives of their subjects. There were such men then. So our general, settled on his property of two thousand souls, lives in pomp, and domineers over his poor neighbors as though they were dependents and buffoons. He has kennels of hundreds of hounds and nearly a hundred dog-boys—all mounted, and in uniform. One day a serf-boy, a little child of eight, threw a stone in play and hurt the paw of the general's favorite hound. ‘Why is my favorite dog lame?’ He is told that the boy threw a stone that hurt the dog's paw. ‘So you did it.’ The general looked the child up and down. ‘Take him.’ He was taken—taken from his mother and kept shut up all night. Early that morning the general comes out on horseback, with the hounds, his dependents, dog-boys, and huntsmen, all mounted around him in full hunting parade.

“The servants are summoned for their edification, and in front of them all stands the mother of the child. The child is brought from the lock-up. It's a gloomy, cold, foggy autumn day, a capital day for hunting. The general orders the child to be undressed; the child is stripped naked. He shivers, numb with terror, not daring to cry.... ‘Make him run,’ commands the general. ‘Run! run!’ shout the dog-boys. The boy runs.... ‘At him!’ yells the general, and he sets the whole pack of hounds on the child. The hounds catch him, and tear him to pieces before his mother's eyes!“

Rejecting the Harmony

| Ivan refuses to accept that the suffering of innocent children is compensated by reward in the afterlife or by any punishment for wrongdoing. The suffering happened and will always remain, and will always be unjust. Ivan’s only conclusion is to reject the God that allowed this to happen and refuse to participate in the rewards of an afterlife that would "justify" the needless suffering of children. |

"Well—what did he deserve? To be shot? To be shot for the satisfaction of our moral feelings? Speak, Alyosha!”

“To be shot,” murmured Alyosha, lifting his eyes to Ivan with a pale, twisted smile.

“Bravo!” cried Ivan, delighted. “If even you say so.... You're a pretty monk! So there is a little devil sitting in your heart, Alyosha Karamazov!”

“What I said was absurd, but—”

“That's just the point, that ‘but’!” cried Ivan. “Let me tell you, novice, that the absurd is only too necessary on earth. The world stands on absurdities, and perhaps nothing would have come to pass in it without them. We know what we know!”

“What do you know?”

“I understand nothing,” Ivan went on, as though in delirium. “I don't want to understand anything now. I want to stick to the fact. I made up my mind long ago not to understand. If I try to understand anything, I shall be false to the fact, and I have determined to stick to the fact.”

“Why are you trying me?” Alyosha cried, with sudden distress. “Will you say what you mean at last?”

“Of course, I will; that's what I've been leading up to…”

Ivan for a minute was silent, his face became all at once very sad.

…

“With my pitiful, earthly, Euclidian understanding, all I know is that there is suffering and that there are none guilty; that cause follows effect, simply and directly; that everything flows and finds its level—but that's only Euclidian nonsense, I know that, and I can't consent to live by it! What comfort is it to me that there are none guilty and that cause follows effect simply and directly, and that I know it?—I must have justice, or I will destroy myself. And not justice in some remote infinite time and space, but here on earth, and that I could see myself. I have believed in it. I want to see it, and if I am dead by then, let me rise again, for if it all happens without me, it will be too unfair. Surely I haven't suffered, simply that I, my crimes and my sufferings, may manure the soil of the future harmony for somebody else. I want to see with my own eyes the hind lie down with the lion and the victim rise up and embrace his murderer. I want to be there when every one suddenly understands what it has all been for. All the religions of the world are built on this longing, and I am a believer. But then there are the children, and what am I to do about them? That's a question I can't answer.

“Listen! If all must suffer to pay for the eternal harmony, what have children to do with it, tell me, please? It's beyond all comprehension why they should suffer, and why they should pay for the harmony. Why should they, too, furnish material to enrich the soil for the harmony of the future? I understand solidarity in sin among men. I understand solidarity in retribution, too; but there can be no such solidarity with children. And if it is really true that they must share responsibility for all their fathers' crimes, such a truth is not of this world and is beyond my comprehension. Some jester will say, perhaps, that the child would have grown up and have sinned, but you see he didn't grow up, he was torn to pieces by the dogs, at eight years old.

“Oh, Alyosha, I am not blaspheming! I understand, of course, what an upheaval of the universe it will be, when everything in heaven and earth blends in one hymn of praise and everything that lives and has lived cries aloud: ‘Thou art just, O Lord, for Thy ways are revealed.’ When the mother embraces the fiend who threw her child to the dogs, and all three cry aloud with tears, ‘Thou art just, O Lord!’ then, of course, the crown of knowledge will be reached and all will be made clear. But what pulls me up here is that I can't accept that harmony. And while I am on earth, I make haste to take my own measures. You see, Alyosha, perhaps it really may happen that if I live to that moment, or rise again to see it, I, too, perhaps, may cry aloud with the rest, looking at the mother embracing the child's torturer, ‘Thou art just, O Lord!’ but I don't want to cry aloud then. While there is still time, I hasten to protect myself, and so I renounce the higher harmony altogether. It's not worth the tears of that one tortured child who beat itself on the breast with its little fist and prayed in its stinking outhouse, with its unexpiated tears to ‘dear, kind God’! It's not worth it, because those tears are unatoned for. They must be atoned for, or there can be no harmony. But how? How are you going to atone for them? Is it possible? By their being avenged? But what do I care for avenging them? What do I care for a hell for oppressors? What good can hell do, since those children have already been tortured? And what becomes of harmony, if there is hell? I want to forgive. I want to embrace. I don't want more suffering. And if the sufferings of children go to swell the sum of sufferings which was necessary to pay for truth, then I protest that the truth is not worth such a price. I don't want the mother to embrace the oppressor who threw her son to the dogs! She dare not forgive him! Let her forgive him for herself, if she will, let her forgive the torturer for the immeasurable suffering of her mother's heart. But the sufferings of her tortured child she has no right to forgive; she dare not forgive the torturer, even if the child were to forgive him! And if that is so, if they dare not forgive, what becomes of harmony? Is there in the whole world a being who would have the right to forgive and could forgive? I don't want harmony. From love for humanity I don't want it. I would rather be left with the unavenged suffering. I would rather remain with my unavenged suffering and unsatisfied indignation, even if I were wrong. Besides, too high a price is asked for harmony; it's beyond our means to pay so much to enter on it. And so I hasten to give back my entrance ticket, and if I am an honest man I am bound to give it back as soon as possible. And that I am doing. It's not God that I don't accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return Him the ticket.”

What does he mean he doesn’t want to know?

Ivan says he has resolved to stick to the fact rather than try to understand. What he means is that the suffering in the world is so terrible that he refuses to seek any justification of it. He believes no rationality could ever measure up to the inevitable, insurmountable suffering of innocent children, and to even attempt to justify it would be callous and cold-hearted. He’d rather simply acknowledge their suffering and face it head on.

“Future Harmony”?

The “future harmony” Ivan is referring to may be heaven in the afterlife, or the paradise promised after the second coming of Christ. He could also be referring to a popular theodicy that claims the Abrahamic God allows suffering in order to allow people to learn some lessons from their suffering and improve in the future.

Ivan's Argument Explained

Ivan says “for love of humanity” he will not participate in the so-called ‘plan of God,’ which he says involves unnecessary suffering. (1b) Benefiting from a system is a form of participation. According to ‘God’s plan’ as Ivan understands it, there is suffering on Earth, but the good people are rewarded with eternal life in heaven and the bad are punished in hell. Accepting God’s invitation to heaven, to future harmony, would make one complicit in the rest of God’s plan, even if you don’t support it. This is similar to the idea that one can benefit from privilege without being aware of one’s privilege or supporting the system that created one’s privilege, or the idea that buying shirts made in sweatshops makes you complicit in the suffering of the laborers who made the shirts.

Ivan says that all we know for sure is that there is suffering and no one is to blame, but that is no comfort. It’s unclear why he says no one is to blame, but we don’t have to agree with that to agree that not all people who suffer have committed some wrongdoing that might justify their suffering. Good, innocent people suffer every day, including children and infants, who couldn’t possibly have committed wrongdoing that justifies the pain and suffering some of them experience. So Ivan says that even if all adults must bear collective blame and suffering to pay for our eternal harmony, children shouldn’t have to pay because they are without sin. The only justification you might give for why children should suffer too, Ivan says, is that they are paying for the sins of their fathers, but he says this is absurd, presumably because the children are their own people and ought not be blamed and punished for something over which they had no control.

Ivan argues that the people who experience the suffering ought to experience the justice; it’s not enough for them to pay for future justice in future generations. So eternal punishment in hell is not good enough, and besides, some of us burning in hell doesn’t seem like harmony to Ivan. What’s more, the suffering of innocent children is too high a price to pay for truth or harmony – it isn’t worth it. So future justice isn’t enough, but justice in this life is also impossible because vengeance doesn’t help the tortured children, and forgiveness is impossible if the victim is dead or a child who doesn’t understand the concept.

We may understand the reason for all this suffering once the harmony is reached, once we are united with God in heaven. But it would be wrong to desire that harmony now because we only can judge based on what we know now, and all we know is that innocent people are suffering.

None of the three ways of redeeming or justifying the suffering we face are successful, so the conclusion must be that at least some of the suffering on Earth is irrational, absurd, and unjustifiable. Conclusion: We should reject this system, including the promise of future harmony. Any system that perpetuates unnecessary suffering ought to be rejected by loving people. So loving people ought to reject ‘God’s plan’ and give back their ticket into heaven, because benefiting from this cruel system makes you complicit in all the unnecessary suffering. |

Summary: A Challenge

| To cement his point, Ivan poses the following thought experiment, meant to summarize the main thrust of his argument: that any God who created this world cannot be good and we ought not partake in the future harmony promised in Christianity. |

“Tell me yourself, I challenge you—answer. Imagine that you are creating a fabric of human destiny with the object of making men happy in the end, giving them peace and rest at last, but that it was essential and inevitable to torture to death only one tiny creature—that baby beating its breast with its fist, for instance—and to found that edifice on its unavenged tears, would you consent to be the architect on those conditions? Tell me, and tell the truth.”

Theodicies

What are Theodicies?

|

A theodicy is a philosophical attempt to reconcile the existence of apparently unnecessary suffering with the belief in a loving and all-powerful deity. Theodicies have been the subject of significant debate and critique over the centuries, and various religious and philosophical traditions have developed different theodicies to address the problem of evil. As you read about some of history's most prominent theodicies, keep in mind Ivan’s declaration that he would rather "stick to the fact" of innocent suffering than seek to understand it. Is there something callous in the very idea of a theodicy? Is some suffering too awful to even attempt to rationalize? |

Free Will

|

This video explores a theodicy based on humans' free will. The basic idea is that free will is an essential aspect of human existence, but it necessarily allows for the existence of evil. If evil did not exist, we would not have the ability to perform immoral actions—but it is precisely this freedom that enables us to understand and appreciate morality and the value of good choices, and so to enjoy our full potential as human beings. |

Responsibility

| Taking the free will defense one step further, a second response is that freedom bestows a responsibility upon humans to assist God in limiting the evil in the world. God created humans as his stewards of creation, and free will provides humans the opportunity to partake in a partnership with God to protect all of creation. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks explains this argument in the video below. |

Evil as a Test

St. Thomas Aquinas draws a distinction between natural evil and moral evil. Natural evil refers to suffering that is not caused by human action, such as natural disasters. Aquinas believes that natural evil is sometimes necessary to maintain order in the universe, which God uses to ensure a just balance. The issue comes when humans attempt to apply their moral standards to God. It is impossible to understand God's goodness because it defies any standard of good we can grasp. Thus, there is no true way to understand why God permits natural evil. Moral evil refers to suffering that results from the intentional actions of humans. Commenting on the Book of Job, Aquinas suggests that the suffering one experiences in this world can be justified by the joys of the afterlife. Evil is necessary to test the goodness of individuals, and those people are rewarded with a blissful afterlife. The eternity of this afterlife versus the relatively short-term suffering in a human's life justifies the existence of evil if it is viewed as a test. |

Acknowledgements

This digital essay was prepared by Blake Ziegler and Sam Kennedy from the University of Notre Dame.

Header Image Credit: Unhappy Crying Kid Young Child Sad Boy Iraq - Max Pixel

Ziegler, Blake and Sam Kennedy. 2022. "Dostoyevsky’s ‘Rebellion’: Reject God." The Notre Dame Philosophy Commons