Why should we listen to, and encourage, dissent?

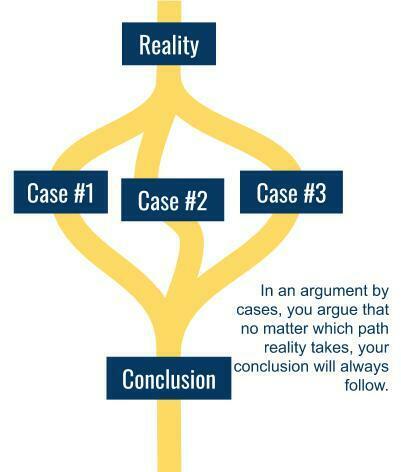

Background: Arguments by Cases

What is it?

In this reading, John Stuart Mill will use a method called argument by cases. In general, it works like this: Consider all scenarios that could possibly be true, then, argue that your conclusion follows no matter which scenario turns out to be true. For example, suppose your friend offers to make a bet with you on the next football game at your school: If your school wins, your friend wins $20. If your school loses, you lose $20. Adept philosopher that you are, you would see the trap and refuse the bet using an argument by cases to show that, no matter what happens in reality, you will lose $20. |

Case 1: Your school wins

If your school wins, your friend wins $20

That means, you lose $20. |

Case 2: Your school loses

If your school loses, you still lose $20. |

Conclusion

|

In both possible cases, you would lose $20. Thus, the conclusion (that you would lose $20 if you take the bet) is true no matter what happens. In this reading, Mill applies this technique to the question of how we should respond when we disagree with someone. If Mill's argument by cases is sound, then when we encounter someone who disagrees with us, it really doesn't matter whether we're right — we should always engage respectfully with opposing views rather than dismissing or suppressing them. |

Introduction

|

John Stuart Mill lived from 1806-1873, during the height of Victorian Era England. This is important because, though he is perhaps best known for his role in developing utilitarianism, Mill was particularly interested in the social and political problems of the Victorian Era, and in much of his work he sought a practical influence. For example, Mill wrote numerous essays about specific social problems such as slavery and the status of women. Mill's book On Liberty explores the limits on the kinds of power society may legitimately exercise over individuals. In his Autobiography, Mill wrote that On Liberty was about “the importance, to man and society, of a large variety in types of character, and of giving full freedom to human nature to expand itself in innumerable and conflicting directions." Thus, On Liberty can be roughly characterized as political philosophy. We will read excerpts from Chapter 2, "Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion." This chapter also contributes to the field of philosophy called epistemology, or the study of knowledge and rationality. Mill argues that disagreement is beneficial—not just socially, but also epistemically: disagreement helps us ultimately believe and appreciate the truth. |

Case #1: You Are Wrong

|

Mill starts the chapter with what he takes to be the obvious truth that governments shouldn’t censor the press. He quickly moves on to a more radical claim: no one should try to stifle or dismiss disagreeing opinions—not even when you find them offensive, when you're virtually certain you're right, or when they're in direct conflict with your way of life. He particularly has in mind protecting minority opinions from 'tyranny of the majority,' but the argument applies whenever someone disagrees with us. Mill's main thesis is that difference of opinion is a very good thing and should therefore be encouraged and engaged in rather than avoided or ignored. His argument proceeds by considering three possible cases: (1) where the common consensus or your own opinion is in reality wrong, (2) where you are in reality right, and (3) where you are partly right, partly wrong. He argues that in all three cases, it is best to engage respectfully and tolerantly, rather than dismissing or suppressing those who disagree. Let’s start with case one. |

First: the opinion which it is attempted to suppress by authority may possibly be true. Those who desire to suppress it, of course deny its truth; but they are not infallible. They have no authority to decide the question for all mankind, and exclude every other person from the means of judging. To refuse a hearing to an opinion, because they are sure that it is false, is to assume that their certainty is the same thing as absolute certainty. All silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility. Its condemnation may be allowed to rest on this common argument, not the worse for being common.

Unfortunately for the good sense of mankind, the fact of their fallibility is far from carrying the weight in their practical judgment, which is always allowed to it in theory; for while every one well knows himself to be fallible, few think it necessary to take any precautions against their own fallibility, or admit the supposition that any opinion of which they feel very certain, may be one of the examples of the error to which they acknowledge themselves to be liable.

Absolute princes, or others who are accustomed to unlimited deference, usually feel this complete confidence in their own opinions on nearly all subjects. People more happily situated, who sometimes hear their opinions disputed, and are not wholly unused to be set right when they are wrong, place the same unbounded reliance only on such of their opinions as are shared by all who surround them, or to whom they habitually defer: for in proportion to a man's want of confidence in his own solitary judgment, does he usually repose, with implicit trust, on the infallibility of "the world" in general. And the world, to each individual, means the part of it with which he comes in contact; his party, his sect, his church, his class of society: the man may be called, by comparison, almost liberal and largeminded to whom it means anything so comprehensive as his own country or his own age. Nor is his faith in this collective authority at all shaken by his being aware that other ages, countries, sects, churches, classes, and parties have thought, and even now think, the exact reverse. He devolves upon his own world the responsibility of being in the right against the dissentient worlds of other people; and it never troubles him that mere accident has decided which of these numerous worlds is the object of his reliance, and that the same causes which make him a Churchman in London, would have made him a Buddhist or a Confucian in Pekin. Yet it is as evident in itself as any amount of argument can make it, that ages are no more infallible than individuals; every age having held many opinions which subsequent ages have deemed not only false but absurd; and it is as certain that many opinions, now general, will be rejected by future ages, as it is that many, once general, are rejected by the present.

We Are All Fallible

Here, Mill is calling out people who walk confidently through life with two competing thoughts: "Everybody makes mistakes" (in other words, we are all fallible) and "I'm certain I'm not making a mistake right now" (in other words, I am infallible when it comes to this idea).

Usually, we're not making a mistake. But those few times when we are and we haven't prepared for it, it can blow up in our faces.

Key Principle: Epistemic Relativism

Here, Mill flirts with (something like) what contemporary epistemologists call epistemic relativism, the claim that what one ought to believe is determined by one's specific context—be that your time period, your culture, or even your individual background and experiences. "The same causes" which make people Christians in England, Mill contends, would have led to them having other beliefs in other places, and being perfectly rationally justified in those beliefs. While Mill is not a relativist, he does think this fact should bring our attention to our fallibility, and the fallibility of the groups and cultures we are a part of.

Case #1 Broken Down

|

(1) People are deeply fallible. Given the diversity of opinion across places and times on a vast array of religious and moral questions, at the very least, we should accept that people in general are very frequently wrong. To be fallible just means there are times where one fails, or is wrong. (2) If people are deeply fallible, then it would not be surprising if you yourself were wrong (and your interlocutor were right). Even if you feel sure you’re right, there’s still a chance you’re wrong. (3) If you are wrong and your interlocutor is right, you stand a better chance of coming around to the right view if you engage in disagreement respectfully. If you constantly interrupt, will you be able to hear their arguments? If you just yell “Wrong!” at the other person, do you think you’re likely to realize they’re right? Of course not. (C) You should engage in disagreement respectfully |

Objection: Relative Certainty

|

You might think that just because a lot of people’s beliefs in past ages about, say, the natural world have proved false, we are less prone to error now. People used to think that water was one of four elements of the universe, but now we know that water is H2O. You might think there’s no way we’ll turn out to be wrong about that. And if someone disagrees and claims that water isn’t H2O — well, they’re just wrong. Objection: Aren’t there particular kinds of questions where we are not fallible, and do we still have to respectfully engage with disagreement if we aren’t very likely to be wrong? Let’s see what Mill says: |

Strange it is, that men should admit the validity of the arguments for free discussion, but object to their being ‘pushed to an extreme’; not seeing that unless the reasons are good for an extreme case, they are not good for any case. Strange that they should imagine that they are not assuming infallibility when they acknowledge that there should be free discussion on all subjects which can possibly be doubtful, but think that some particular principle or doctrine should be forbidden to be questioned because it is so certain, that is, because they are certain that it is certain. To call any proposition certain, while there is any one who would deny its certainty if permitted, but who is not permitted, is to assume that we ourselves, and those who agree with us, are the judges of certainty, and judges without hearing the other side.

If even the Newtonian philosophy were not permitted to be questioned, mankind could not feel as complete assurance of its truth as they now do. The beliefs which we have most warrant for, have no safeguard to rest on, but a standing invitation to the whole world to prove them unfounded. If the challenge is not accepted, or is accepted and the attempt fails, we are far enough from certainty still; but we have done the best that the existing state of human reason admits of; we have neglected nothing that could give the truth a chance of reaching us: if the lists are kept open, we may hope that if there be a better truth, it will be found when the human mind is capable of receiving it; and in the meantime we may rely on having attained such approach to truth, as is possible in our own day. This is the amount of certainty attainable by a fallible being, and this the sole way of attaining it.

|

So Mill thinks that only by being open to challenge can we ever have some certainty a belief is true. That's why experiments are replicated and revised constantly in science, and nothing is ever considered proven beyond doubt—not even Newton's laws of motion! Mill does allow one caveat to his claim, though: mathematical truths. For these, we still ought to know why they are true, but we need not consider the opposition so much. Here’s where he explains this: |

But, someone may say, ‘Let them be taught the grounds of their opinions. It does not follow that opinions must be merely parroted because they are never heard controverted. Persons who learn geometry do not simply commit the theorems to memory, but understand and learn likewise the demonstrations; and it would be absurd to say that they remain ignorant of the grounds of geometrical truths, because they never hear anyone deny, and attempt to disprove them.’ Undoubtedly: and such teaching suffices on a subject like mathematics, where there is nothing at all to be said on the wrong side of the question. The peculiarity of the evidence of mathematical truths is that all the argument is on one side. There are no objections, and no answers to objections. But on every subject on which difference of opinion is possible, the truth depends on a balance to be struck between two sets of conflicting reasons.

Objection: Usefulness

| What about those beliefs that are so central to who you are or who your community is that you feel you can't live without them—for example, belief in God, or belief in the rights to life and liberty? Must we leave even these open to disagreement? Mill has an answer, and it might not be the one you'd hoped for: |

In the present age—which has been described as ‘destitute of faith, but terrified at scepticism’,—in which people feel sure, not so much that their opinions are true, as that they should not know what to do without them—the claims of an opinion to be protected from public attack are rested not so much on its truth, as on its importance to society. There are, it is alleged, certain beliefs, so useful, not to say indispensable to well-being, that it is as much the duty of governments to uphold those beliefs, as to protect any other of the interests of society.

In a case of such necessity, and so directly in the line of their duty, something less than infallibility may, it is maintained, warrant, and even bind, governments, to act on their own opinion, confirmed by the general opinion of mankind. It is also often argued, and still oftener thought, that none but bad men would desire to weaken these salutary beliefs; and there can be nothing wrong, it is thought, in restraining bad men, and prohibiting what only such men would wish to practise. This mode of thinking makes the justification of restraints on discussion not a question of the truth of doctrines, but of their usefulness; and flatters itself by that means to escape the responsibility of claiming to be an infallible judge of opinions. But those who thus satisfy themselves, do not perceive that the assumption of infallibility is merely shifted from one point to another. The usefulness of an opinion is itself a matter of opinion: as disputable, as open to discussion and requiring discussion as much, as the opinion itself. There is the same need of an infallible judge of opinions to decide an opinion to be noxious, as to decide it to be false, unless the opinion condemned has full opportunity of defending itself. And it will not do to say that the heretic may be allowed to maintain the utility or harmlessness of his opinion, though forbidden to maintain its truth. The truth of an opinion is part of its utility. If we would know whether or not it is desirable that a proposition should be believed, is it possible to exclude the consideration of whether or not it is true? And in point of fact, when law or public feeling do not permit the truth of an opinion to be disputed, they are just as little tolerant of a denial of its usefulness. The utmost they allow is an extenuation of its absolute necessity or of the positive guilt of rejecting it.

|

You might have thought that by pointing to usefulness rather than truth you had avoided the assumption of infallibility. But Mill says even the usefulness of an opinion is a matter of opinion. You might think belief in God is necessary for a good life, but others may not. Or consider the belief that vaccines are good for public health. This belief is useful only if it is true. One cannot be separated from the other. Thus, even our most fundamental beliefs must remain open to doubt, to disagreement, and to other ways of life. |

Case #2: You Are Right

|

There are still two more cases to consider for Mill's argument. Here’s the second one: |

Let us now pass to the second division of the argument, and dismissing the Supposition that any of the received opinions may be false, let us assume them to be true, and examine into the worth of the manner in which they are likely to be held, when their truth is not freely and openly canvassed. However unwillingly a person who has a strong opinion may admit the possibility that his opinion may be false, he ought to be moved by the consideration that however true it may be, if it is not fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed, it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth.

There is a class of persons (happily not quite so numerous as formerly) who think it enough if a person assents undoubtingly to what they think true, though he has no knowledge whatever of the grounds of the opinion, and could not make a tenable defence of it against the most superficial objections. Such persons, if they can once get their creed taught from authority, naturally think that no good, and some harm, comes of its being allowed to be questioned. Where their influence prevails, they make it nearly impossible for the received opinion to be rejected wisely and considerately, though it may still be rejected rashly and ignorantly; for to shut out discussion entirely is seldom possible, and when it once gets in, beliefs not grounded on conviction are apt to give way before the slightest semblance of an argument. Waiving, however, this possibility—assuming that the true opinion abides in the mind, but abides as a prejudice, a belief independent of, and proof against, argument—this is not the way in which truth ought to be held by a rational being. This is not knowing the truth. Truth, thus held, is but one superstition the more, accidentally clinging to the words which enunciate a truth.

If the intellect and judgment of mankind ought to be cultivated, on what can these faculties be more appropriately exercised by any one, than on the things which concern him so much that it is considered necessary for him to hold opinions on them? If the cultivation of the understanding consists in one thing more than in another, it is surely in learning the grounds of one's own opinions. Whatever people believe, on subjects on which it is of the first importance to believe rightly, they ought to be able to defend against at least the common objections.

The greatest orator, save one, of antiquity, has left it on record that he always studied his adversary's case with as great, if not with still greater, intensity than even his own. What Cicero practised as the means of forensic success, requires to be imitated by all who study any subject in order to arrive at the truth. He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. The rational position for him would be suspension of judgment, and unless he contents himself with that, he is either led by authority, or adopts, like the generality of the world, the side to which he feels most inclination.

Ninety-nine in a hundred of what are called educated men are in this condition, even of those who can argue fluently for their opinions. Their conclusion may be true, but it might be false for anything they know: they have never thrown themselves into the mental position of those who think differently from them, and considered what such persons may have to say; and consequently they do not, in any proper sense of the word, know the doctrine which they themselves profess. They do not know those parts of it which explain and justify the remainder; the considerations which show that a fact which seemingly conflicts with another is reconcilable with it, or that, of two apparently strong reasons, one and not the other ought to be preferred. All that part of the truth which turns the scale, and decides the judgment of a completely informed mind, they are strangers to; nor is it ever really known, but to those who have attended equally and impartially to both sides, and endeavored to see the reasons of both in the strongest light. So essential is this discipline to a real understanding of moral and human subjects, that if opponents of all important truths do not exist, it is indispensable to imagine them and supply them with the strongest arguments which the most skillful devil's advocate can conjure up.

To be a 'rational being' means having the ability to reason: to think critically, imagine possible futures and choose between them, and make arguments. Mill argues that rational beings must know the why of their beliefs, not just the what.

Case #2 Broken Down

|

Even when we already know the truth (and hence don’t need to have our errors corrected), Mill argues that we need to engage with disagreement in order to appreciate and really know what we believe to be true. It is only through engaging with people who earnestly believe and defend alternate views that we can really know our own. We might try to formalize the argument as follows: (1) Really knowing something requires being able to give reasons for it and answer objections. If you’re not able to say WHY you believe something, can you really say you believe it? If you’re a rational person, one that listens to reason, then Mill says you can’t (See the example in the next section). (2) The only way to become skillful in giving reasons for our views and answering objections is to encounter and take seriously real people who earnestly object to our views. This is how we practice arguing and get better at it! (C) You should engage in disagreement respectfully. |

Example: The Nicene Creed

|

Religious worship often involves reciting prayers, creeds, or mantras. An example from Christian liturgy is the Nicene Creed. But if you recite a prayer or creed regularly, without ever encountering challenges to its truth, will you fully appreciate it? Will you really understand what it means or why you recite it? Here's a part of the Nicene Creed, making claims about Jesus: I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; through him all things were made. On reflection, these claims are rather complex and strange. What does the claim "Light from Light" mean, and what does it add to the claim "God from God"? What are Christians saying they believe when they say Jesus is "consubstantial" with the Father? These are tricky questions. And yet, it can get pretty easy after years of saying these things to just let the words roll off your tongue without reflection. Here’s what Mill says about this exact example: |

The fact, however, is, that not only the grounds of the opinion are forgotten in the absence of discussion, but too often the meaning of the opinion itself. The words which convey it, cease to suggest ideas, or suggest only a small portion of those they were originally employed to communicate. Instead of a vivid conception and a living belief, there remain only a few phrases retained by rote; or, if any part, the shell and husk only of the meaning is retained, the finer essence being lost. The great chapter in human history which this fact occupies and fills, cannot be too earnestly studied and meditated on. It is illustrated in the experience of almost all ethical doctrines and religious creeds. They are all full of meaning and vitality to those who originate them, and to the direct disciples of the originators. Their meaning continues to be felt in undiminished strength, and is perhaps brought out into even fuller consciousness, so long as the struggle lasts to give the doctrine or creed an ascendency over other creeds. At last it either prevails, and becomes the general opinion, or its progress stops; it keeps possession of the ground it has gained, but ceases to spread further. When either of these results has become apparent, controversy on the subject flags, and gradually dies away. The doctrine has taken its place, if not as a received opinion, as one of the admitted sects or divisions of opinion: those who hold it have generally inherited, not adopted it; and conversion from one of these doctrines to another, being now an exceptional fact, occupies little place in the thoughts of their professors. Instead of being, as at first, constantly on the alert either to defend themselves against the world, or to bring the world over to them, they have subsided into acquiescence, and neither listen, when they can help it, to arguments against their creed, nor trouble dissentients (if there be such) with arguments in its favor. From this time may usually be dated the decline in the living power of the doctrine.

When it has come to be an hereditary creed, and to be received passively, not actively—when the mind is no longer compelled, in the same degree as at first, to exercise its vital powers on the questions which its belief presents to it, there is a progressive tendency to forget all of the belief except the formularies, or to give it a dull and torpid assent, as if accepting it on trust dispensed with the necessity of realizing it in consciousness, or testing it by personal experience; until it almost ceases to connect itself at all with the inner life of the human being. Then are seen the cases, so frequent in this age of the world as almost to form the majority, in which the creed remains as it were outside the mind, encrusting and petrifying it against all other influences addressed to the higher parts of our nature; manifesting its power by not suffering any fresh and living conviction to get in, but itself doing nothing for the mind or heart, except standing sentinel over them to keep them vacant.

Case #3: You Are Partly Right

| This is the final and most common case: You are partly right, partly wrong. Let’s take a look at the passage: |

We have hitherto considered only two possibilities: that the received opinion may be false, and some other opinion, consequently, true; or that, the received opinion being true, a conflict with the opposite error is essential to a clear apprehension and deep feeling of its truth. But there is a commoner case than either of these; when the conflicting doctrines, instead of being one true and the other false, share the truth between them; and the nonconforming opinion is needed to supply the remainder of the truth, of which the received doctrine embodies only a part.

Popular opinions, on subjects not palpable to sense, are often true, but seldom or never the whole truth. They are a part of the truth; sometimes a greater, sometimes a smaller part, but exaggerated, distorted, and disjoined from the truths by which they ought to be accompanied and limited. Heretical opinions, on the other hand, are generally some of these suppressed and neglected truths, bursting the bonds which kept them down, and either seeking reconciliation with the truth contained in the common opinion, or fronting it as enemies, and setting themselves up, with similar exclusiveness, as the whole truth.

Unless opinions favorable to democracy and to aristocracy, to property and to equality, to co-operation and to competition, to luxury and to abstinence, to sociality and individuality, to liberty and discipline, and all the other standing antagonisms of practical life, are expressed with equal freedom, and enforced and defended with equal talent and energy, there is no chance of both elements obtaining their due; one scale is sure to go up, and the other down.

Truth, in the great practical concerns of life, is so much a question of the reconciling and combining of opposites, that very few have minds sufficiently capacious and impartial to make the adjustment with an approach to correctness, and it has to be made by the rough process of a struggle between combatants fighting under hostile banners. On any of the great open questions just enumerated, if either of the two opinions has a better claim than the other, not merely to be tolerated, but to be encouraged and countenanced, it is the one which happens at the particular time and place to be in a minority. That is the opinion which, for the time being, represents the neglected interests, the side of human well-being which is in danger of obtaining less than its share. I am aware that there is not, in this country, any intolerance of differences of opinion on most of these topics. They are adduced to show, by admitted and multiplied examples, the universality of the fact, that only through diversity of opinion is there, in the existing state of human intellect, a chance of fair play to all sides of the truth. When there are persons to be found, who form an exception to the apparent unanimity of the world on any subject, even if the world is in the right, it is always probable that dissentients have something worth hearing to say for themselves, and that truth would lose something by their silence.

Case #3 Broken Down

|

In this passage, Mill considers the final case, and the one he believes is most common: that both sides of the issue are partly right, partly wrong. Here is the argument outlined: (1) When your view is only partially true, you can make progress by being informed by either those with (purely) true opinion or those with a complementary partial grasp of truth A complementary partial grasp is held by anyone who grasps a part of the truth you do not. (2) It is often the case that your views are only partially true. The truth often lies somewhere in the "middle" of two opposing views. Even if you are right in your own belief, there is likely to be a piece of the opposing story that is also true. People rarely firmly believe things that are ENTIRELY built on lies and falsity. (3) You often can make progress toward the full truth by being informed by those who hold another piece of the truth. This follows from (1) and (2). (4) You won't be informed by those who hold another piece of the truth unless you engage in disagreement respectfully. (C) You should engage in disagreement respectfully. |

Blind Men and the Elephant

There is an Indian folk tale that gets at what Mill is talking about here. In it, six blind men who have never encountered an elephant before are led to examine the animal by touching it. They each touch a different part of the elephant, and consequently each comes up with a completely different idea of what it is like: one believes it is like a rope, another like a tree, and so on. Only through dialogue with each other do they realize the whole truth.

This is what Mill is arguing in this passage: We all have experiences and backgrounds that lead us to see part of the truth, but not all of it. Sometimes, even a whole community or nation sees only that part of the truth, to the point where it seems like it is the whole truth. But there is always another part of the elephant, of the world, that you haven't explored, and you need to engage with people with different experiences and backgrounds to discover this unseen part, to get to the whole truth.

What Should We Do?

Doing the Best We Can

| So what now? Should we just never act on our own opinions because they might be wrong? Should we never take sides on an issue because both sides are usually partially right? Luckily, Mill has an answer to these worries: |

I do not pretend that the most unlimited use of the freedom of enunciating all possible opinions would put an end to the evils of religious or philosophical sectarianism. Every truth which men of narrow capacity are in earnest about, is sure to be asserted, inculcated, and in many ways even acted on, as if no other truth existed in the world, or at all events none that could limit or qualify the first. I acknowledge that the tendency of all opinions to become sectarian is not cured by the freest discussion, but is often heightened and exacerbated thereby.

| Some psychological research confirms this view: Often, when confronted with the opposing viewpoints facts and data, people get defensive and actually become more sure of the truth of their side than before. Is this reflected in your own experience? |

The truth which ought to have been, but was not seen, being rejected all the more violently because proclaimed by persons regarded as opponents. But it is not on the impassioned partisan, it is on the calmer and more disinterested bystander, that this collision of opinions works its salutary effect.

Not the violent conflict between parts of the truth, but the quiet suppression of half of it, is the formidable evil: there is always hope when people are forced to listen to both sides; it is when they attend only to one that errors harden into prejudices, and truth itself ceases to have the effect of truth, by being exaggerated into falsehood.

Political Applications

|

Mill’s arguments here might make us a little uncomfortable. After all, respectfully engaging disagreement seems all well and good when what we’re disagreeing about is something abstract or trivial. But there are cases that seem so settled, where the public seems to have an urgent interest in disregarding disagreement. Should we make plans quickly to address man-made climate change? Should we implement affirmative action policies? Should parents vaccinate their children? Many people think so, and they think we should disregard the opinions of those who disagree. After all, they might say, there are questions that we can settle with a high degree of reliability that are of enormous practical import. It seems that Mill, however, would caution them. Fighting climate change is only important if there really is climate change. And that is precisely what some people deny. Closing Question: What kind of respectful engagement with disagreement might Mill recommend on urgent political questions?Would this involve suspending judgment? Suspending the enactment of policies? Giving people the right to be heard, and using their voice as an opportunity to clarify our own convictions? |

Acknowledgements

|

This digital essay was prepared by Sam Kennedy and Laura Callahan from the University of Notre Dame. Cover Image credit: "Two Bulls Clash Antlers" by USFWS Mountain Prairie is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Callahan, Laura and Sam Kennedy. 2021. "J.S. Mill’s On Liberty: Seek Disagreement." The Notre Dame Philosophy Commons. |