Is it ever ok to believe something without sufficient evidence?

Introduction

Who Was William James?

|

What is Pragmatism?

|

In philosophy, James played a foundational role in the development and popularization of pragmatism, a philosophical approach that emphasizes the practical consequences and utility of beliefs as the basis for determining their truth or value. Pragmatists like James urged a shift from abstract theorizing to empirical examination of how beliefs function in real-life situations to satisfy human needs and desires. This approach marked a departure from traditional theoretical frameworks, in which the truth or falsehood of a belief was seen as independent of its practical consequences. |

Clifford's Challenge

|

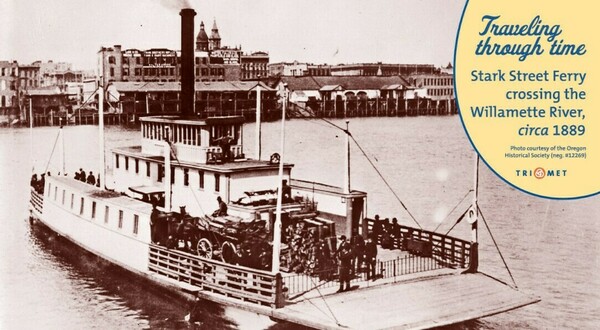

In ‘The Will to Believe,’ James is partly responding to Clifford's The Ethics of Belief (1877) in which Clifford defends an evidentialist theory of justification: that you can rationally hold a belief only if there is enough evidence to support it, and you should only be as confident in the belief as your evidence warrants. Clifford grew up a devout Christian, but later became an atheist and an outspoken critic of religion. In The Ethics of Belief, Clifford argues that belief without sufficient evidence is always immoral. To demonstrate this, Clifford uses the example of an owner of a very old ferry. The owner wonders whether it is still seaworthy, but because the repair costs are so high, he convinces himself to believe the ship is in working condition, and sends it off. Of course, the ship sinks, taking all the crew and the passengers with it.  Clifford argues that the owner is responsible for their deaths, and it was immoral to believe the ship was seaworthy without sufficient evidence. He extrapolates this argument to all beliefs, including religion. If there is not sufficient rational evidence for a religion (which Clifford thinks there isn’t), then it is immoral to believe in one. James disagrees with Clifford and defends a non-evidentialist theory, contending that we may be rational in holding a belief even if we don't have sufficient evidence for it. James originally delivered "The Will to Believe" as a lecture in 1896, and published it soon afterwards. He explains that "The Will to Believe" is an essay on the "justification of faith, a defense of our right to adopt a believing attitude in religious matters, in spite of the fact that our merely logical intellect may not have been coerced." Many understand James as defending a kind of fideism - the idea that faith is in some sense independent from (and sometimes perhaps even opposed to) reason. James argues that we may be justified in adopting a belief even if we don't have enough prior evidence in support of it, and in some cases, (a) we may have access to supporting evidence only after we have adopted the belief, or (b) our adoption of the belief may make the belief true. For James, religious convictions are paradigm examples of such beliefs. |

Video Summary

Objectivity Is Impossible

|

In Section 6 of "The Will to Believe," James dispenses with the notion that humans can ever access objective truth, meaning facts about reality that are true in all places, for all things, at all times, independent of whether humans know them or assert them as truth. Consider the classic puzzle: If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? At first, this may seem like a silly question: of course the tree makes a sound! But how do you know? Nobody is around to hear it, after all. Whether the tree did or did not make a sound is an objective truth, a fact about reality independent of humans knowing or making a claim about it. And, in this case, it doesn’t seem like we have any access to that truth.  James argues that all truth is like that tree falling. Here’s how he puts it: |

Objective evidence and certitude are doubtless very fine ideals to play with, but where on this moonlit and dream-visited planet are they found? I am, therefore, myself a complete empiricist so far as my theory of human knowledge goes. I live, to be sure, by the practical faith that we must go on experiencing and thinking over our experience, for only thus can our opinions grow more true; but to hold any one of them—I absolutely do not care which—as if it never could be reinterpretable or corrigible, I believe to be a tremendously mistaken attitude, and I think that the whole history of philosophy will bear me out.

There is but one indefectibly certain truth, and that is the truth that pyrrhonistic scepticism itself leaves standing—the truth that the present phenomenon of consciousness exists. That, however, is the bare starting-point of knowledge, the mere admission of a stuff to be philosophized about. The various philosophies are but so many attempts at expressing what this stuff really is.

And if we repair to our libraries what disagreement do we discover! Where is a certainly true answer found? Apart from abstract propositions of comparison (such as two and two are the same as four), propositions which tell us nothing by themselves about concrete reality, we find no proposition ever regarded by any one as evidently certain that has not either been called a falsehood, or at least had its truth sincerely questioned by some one else.

No concrete test of what is really true has ever been agreed upon. Some make the criterion external to the moment of perception, putting it either in revelation, the consensus gentium (the agreement of all nations], the instincts of the heart, or the systematized experience of the race. Others make the perceptive moment its own test—Descartes, for instance, with his clear and distinct ideas guaranteed by the veracity of God; Reid with his 'common-sense;' and Kant with his forms of synthetic judgment a priori. The inconceivability of the opposite; the capacity to be verified by sense; the possession of complete organic unity or self-relation, realized when a thing is its own other—are standards which, in turn, have been used. The much lauded objective evidence is never triumphantly there; it is a mere aspiration or Grenzbegriff [limit or ideal notion] marking the infinitely remote ideal of our thinking life. To claim that certain truths now possess it, is simply to say that when you think them true and they are true, then their evidence is objective, otherwise it is not. But practically one's conviction that the evidence one goes by is of the real objective brand, is only one more subjective opinion added to the lot.

For what a contradictory array of opinions have objective evidence and absolute certitude been claimed! The world is rational through and through—its existence is an ultimate brute fact; there is a personal God—a personal God is inconceivable; there is an extra-mental physical world immediately known—the mind can only know its own ideas; a moral imperative exists—obligation is only the resultant of desires; a permanent spiritual principle is in every one—there are only shifting states of mind—there is an endless chain of causes—there is an absolute first cause—an eternal necessity—a freedom—a purpose—no purpose—a primal One—a primal Many—a universal continuity—an essential discontinuity in things—an infinity—no infinity.

There is this; there is that; there is indeed nothing which some one has not thought absolutely true, while his neighbor deemed it absolutely false; and not an absolutist among them seems ever to have considered that the trouble may all the time be essential, and that the intellect, even with truth directly in its grasp, may have no infallible signal for knowing whether it be truth or no. When, indeed, one remembers that the most striking practical application to life of the doctrine of objective certitude has been the conscientious labors of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, one feels less tempted than ever to lend the doctrine a respectful ear.

But please observe, now, that when as empiricists we give up the doctrine of objective certitude, we do not thereby give up the quest or hope of truth itself. We still pin our faith on its existence, and still believe that we gain an ever better position towards it by systematically continuing to roll up experiences and think.

Our great difference from the scholastic lies in the way we face. The strength of his system lies in the principles, the origin, the terminus a quo [the beginning point] of his thought; for us the strength is in the outcome, the upshot, the terminus ad quem [the end result]. Not where it comes from but what it leads to is to decide. It matters not to an empiricist from what quarter an hypothesis may come to him: he may have acquired it by fair means or by foul; passion may have whispered or accident suggested it; but if the total drift of thinking continues to confirm it, that is what he means by its being true.

Empiricists believe that truth is known through sense experience, not from rational, theoretical thought. All pragmatists are empiricists, as are most science-oriented philosophers. Other famous philosophers that lean empiricist include John Locke, David Hume, and arguably Aristotle, although the term wasn't around back then.

Pyrrhonistic Skepticism, introduced by Ancient Greek philosopher Pyrrho of Elis, is a philosophy which proposes that one should suspend judgment about matters that are 'non-evident' (most of them), in order to reach ataraxia - a state of equanimity or peace of mind.

“That the present phenomenon of consciousness exists” as the one truth we know for certain is a call back to Descartes’ cogito ("I think, therefore I am").

You don’t really have to know what all these are references to. The point is James thinks they are all a load of hooey.

Objective truths aren't accessible...

| James argues that, apart from the truth that consciousness exists, the history of ideas has shown that (1) people cannot agree on the appropriate test of whether something is true or not, (2) people throughout history have claimed a host of contradictory things as objective truths, (3) claims to objective certitude often lead to violent consequences that are later regretted. |

But that doesn't mean we should stop searching.

| In the face of this lack of certainty, some might become nihilists, and claim “everything is permitted.” But James backs us away from this abyss. He and the pragmatists (and also Clifford and the skeptics) believe we can get closer to objective truth by systematically examining our experiences, and this is valuable even if we never fully get there. |

A new definition of truth

| In the final paragraph of this excerpt, James proposes we throw away the idea “things are true only if they rest on an objectively certain foundation of evidence” and replace it with “things are true only if ‘the total drift of thinking continues to affirm it.’” This pragmatic theory of truth may sound strange at first, but it is basically how Western science works. Consider the definitions of hypotheses, models, theories, and laws – they’re all true only as long as there’s no damning counterevidence. James is simply arguing that we should think of all truths like the truths in science. |

Conditions for Leaping

Ethics of Belief

|

With the hope of objectivity out the window, let’s turn back to the debate between James and Clifford: In the face of insufficient evidence, is it ever justifiable to believe something is true? In Sections 1-4, James lays out the conditions under which he believes it would be justifiable to "take a leap of faith" even when we lack evidence for the truth of our belief. He argues that leaps are justifiable in circumstances where the choices are live, and the question at hand is forced and momentous. |

Live

A belief is live for you if it is at least minimally appealing (ex: either choose to be an agnostic or be a Christian). A belief is dead if there is no possible way you could see yourself genuinely believing it (ex: either choose to believe that the flying spaghetti monster exists or that pigs can fly). |

Forced

A choice is forced if choosing is unavoidable (ex: choosing to practice Catholicism or not—if you attempt to avoid choosing, you end up implicitly choosing the latter option). A choice is not forced if you can avoid it (ex: I tell you “love me or hate me.” You can avoid choosing by remaining indifferent to me). |

Momentous

A choice is momentous if it is unique, has significant stakes, and/or is irreversible (ex: choose whether or not to travel to the North Pole with your professor—this may be your only chance in your lifetime, and it has serious consequences for your life). A choice is trivial if it is not unique, has minimal stakes, and/or is reversible (ex: choose whether or not to take a nap right now. You could always take one later, and it’s not that important of a choice). |

Why Take the Leap?

| So now we know the conditions under which James thinks it is morally permissible to take a leap of faith, but still we ought to ask ourselves: Why do it? Why take a risk on a religion, a relationship, a career opportunity, etc. when we aren’t sure if it’ll work out or if it is really true? Here’s what James says in Section 7: |

There are two ways of looking at our duty in the matter of opinion. Believe truth! Shun error! These, we see, are two materially different laws; and by choosing between them we may end by coloring differently our whole intellectual life. We may regard the chase for truth as paramount, and the avoidance of error as secondary; or we may, on the other hand, treat the avoidance of error as more imperative, and let truth take its chance. Clifford, in the instructive passage which I have quoted, exhorts us to the latter course. Believe nothing, he tells us, keep your mind in suspense forever, rather than by closing it on insufficient evidence incur the awful risk of believing lies. You, on the other hand, may think that the risk of being in error is a very small matter when compared with the blessings of real knowledge, and be ready to be duped many times in your investigation rather than postpone indefinitely the chance of guessing true. I myself find it impossible to go with Clifford. We must remember that these feelings of our duty about either truth or error are in any case only expressions of our passional life. Biologically considered, our minds are as ready to grind out falsehood as veracity, and he who says, " Better go without belief forever than believe a lie!" merely shows his own preponderant private horror of becoming a dupe. He may be critical of many of his desires and fears, but this fear he slavishly obeys. He cannot imagine any one questioning its binding force. For my own part, I have also a horror of being duped; but I can believe that worse things than being duped may happen to a man in this world: so Clifford's exhortation has to my ears a thoroughly fantastic sound. It is like a general informing his soldiers that it is better to keep out of battle forever than to risk a single wound. Not so are victories either over enemies or over nature gained. Our errors are surely not such awfully solemn things. In a world where we are so certain to incur them in spite of all our caution, a certain lightness of heart seems healthier than this excessive nervousness on their behalf. At any rate, it seems the fittest thing for the empiricist philosopher.

Turn now to a certain class of questions of fact, questions concerning personal relations, states of mind between one man and another. Do you like me or not?—for example. Whether you do or not depends, in countless instances, on whether I meet you half-way, am willing to assume that you must like me, and show you trust and expectation. The previous faith on my part in your liking's existence is in such cases what makes your liking come. But if I stand aloof, and refuse to budge an inch until I have objective evidence, until you shall have done something apt, as the absolutists say, ten to one your liking never comes. The desire for a certain kind of truth in certain cases brings about that special truth's existence. Who gains promotions, boons, appointments, but the man in whose life they are seen to play the part of live hypotheses, who discounts them, sacrifices other things for their sake before they have come, and takes risks for them in advance? His faith acts on the powers above him as a claim, and creates its own verification.

A social organism of any sort whatever, large or small, is what it is because each member proceeds to his own duty with a trust that the other members will simultaneously do theirs. Wherever a desired result is achieved by the co-operation of many independent persons, its existence as a fact is a pure consequence of the precursive faith in one another of those immediately concerned. A government, an army, a commercial system, a ship, a college, an athletic team, all exist on this condition, without which not only is nothing achieved, but nothing is even attempted. A whole train of passengers (individually brave enough) will be looted by a few highwaymen, simply because the latter can count on one another, while each passenger fears that if he makes a movement of resistance, he will be shot before any one else backs him up. If we believed that the whole car-full would rise at once with us, we should each severally rise, and train robbing would never even be attempted. There are, then, cases where a fact cannot come at all unless a preliminary faith exists in its coming. And where faith in a fact can help create the fact, that would be an insane logic which should say that faith running ahead of scientific evidence is the 'lowest kind of immorality ' into which a thinking being can fall. Yet such is the logic by which our scientific absolutists pretend to regulate our lives.

'Take the Leap' Argument Broken Down

|

Above, we talked about how Clifford defends an evidentialist theory in claiming that we should only hold a belief when we have enough evidence to support it, and we ought to withhold belief (or remain agnostic) when we lack or have insufficient evidence. James focuses on arguing against the second half of this claim, what is sometimes called the Agnostic Imperative: that we should remain agnostic when we have insufficient evidence, that it would be irrational not to. Recall that James defends a non-evidentialist theory in claiming that we can sometimes rationally hold a belief even when we don't have sufficient evidence to support it. James argues against Clifford here by highlighting the fact that Clifford's approach embodies a kind of approach or 'stance' towards beliefs that has some troublesome implications. Here's an outline of James' argument:

Stance #1: avoid error at all costs, even if it means sometimes missing out on the truth Analogy: a general tells keeps his soldiers out of battle forever so they don't risk getting wounded - but in doing so, the soldiers miss out on actually fighting the battle; Sam never asks Alex out for fear of rejection - but in doing so, Sam misses out on the fact that Alex might say yes. Stance #2: seek the truth, even if it means sometimes risking error Analogy: the goal of winning the battle is so important that the general sends his soldiers into battle, even though that means they risk getting wounded; it's important enough to Sam to figure out if Alex is interested, so Sam asks Alex out even though it means risking rejection.

Remaining agnostic in the face of insufficient evidence helps us avoid error, while holding a belief without sufficient evidence may sometimes lead us to the truth (but may also sometimes lead us to error).

Examples James uses:

(C) Clifford's Agnostic Imperative restricts our access to truth and is therefore inadequate. |

What James' Argument ISN'T saying

|

It's important to note that James' argument here does not claim any of the following things: a. that error is desirable or unproblematic James still thinks error is undesirable and problematic, he just doesn't think it is SO undesirable and problematic that it should dissuade us from seeking the truth. b. that we should disregard the evidence when forming our beliefs James still thinks we should form many of our beliefs on the basis of evidence, here he specifically addresses cases where we don't have enough evidence to do that. c. that 'anything goes' in situations where we can rationally form beliefs without sufficient evidence James still thinks there are important criteria and restrictions about what we can believe in these situations, which he addresses in sections 8 and 9. |

Pragmatism and Religious Faith

| After arguing against Clifford's proposal, James goes on to explain in Section 10 why and how we should prioritize 'seeking the truth.’ He specifically focuses on how his proposal is important in the realm of religious belief in this beautifully composed section. |

In truths dependent on our personal action, then, faith based on desire is certainly a lawful and possibly an indispensable thing. But now, it will be said, these are all childish human cases, and have nothing to do with great cosmic matters, like the question of religious faith. Let us then pass on to that. Religions differ so much in their accidents that in discussing the religious question we must make it very generic and broad. What then do we now mean by the religious hypothesis?

Is Religious Choice Live, Forced, and Momentous?

Now, let us consider what the logical elements of this situation are in case the religious hypothesis in both its branches be really true. (Of course, we must admit that possibility at the outset. If we are to discuss the question at all, it must involve a living option. If for any of you religion be a hypothesis that cannot, by any living possibility be true, then you need go no farther. I speak to the 'saving remnant' alone.) So proceeding, we see, first that religion offers itself as a momentous option. We are supposed to gain, even now, by our belief, and to lose by our nonbelief, a certain vital good. Secondly, religion is a forced option, so far as that good goes. We cannot escape the issue by remaining sceptical and waiting for more light, because, although we do avoid error in that way if religion be untrue, we lose the good, if it be true, just as certainly as if we positively chose to disbelieve.

Is It Better to Shun Error or Believe Truth?

It is as if a man should hesitate indefinitely to ask a certain woman to marry him because he was not perfectly sure that she would prove an angel after he brought her home. Would he not cut himself off from that particular angel-possibility as decisively as if he went and married some one else? Scepticism, then, is not avoidance of option; it is option of a certain particular kind of risk. Better risk loss of truth than chance of error,-that is your faith-vetoer's exact position. He is actively playing his stake as much as the believer is; he is backing the field against the religious hypothesis, just as the believer is backing the religious hypothesis against the field. To preach scepticism to us as a duty until 'sufficient evidence' for religion be found, is tantamount therefore to telling us, when in presence of the religious hypothesis, that to yield to our fear of its being error is wiser and better than to yield to our hope that it may be true. It is not intellect against all passions, then; it is only intellect with one passion laying down its law.

And by what, forsooth, is the supreme wisdom of this passion warranted? Dupery for dupery, what proof is there that dupery through hope is so much worse than dupery through fear? I, for one, can see no proof; and I simply refuse obedience to the scientist's command to imitate his kind of option, in a case where my own stake is important enough to give me the right to choose my own form of risk. If religion be true and the evidence for it be still insufficient, I do not wish, by putting your extinguisher upon my nature (which feels to me as if it had after all some business in this matter), to forfeit my sole chance in life of getting upon the winning side—that chance depending, of course, on my willingness to run the risk of acting as if my passional need of taking the world religiously might be prophetic and right.

Now, to most of us religion comes in a still further way that makes a veto on our active faith even more illogical. The more perfect and more eternal aspect of the universe is represented in our religions as having personal form. The universe is no longer a mere It to us, but a Thou, if we are religious; and any relation that may be possible from person to person might be possible here. For instance, although in one sense we are passive portions of the universe, in another we show a curious autonomy, as if we were small active centres on our own account. We feel, too, as if the appeal of religion to us were made to our own active good-will, as if evidence might be forever withheld from us unless we met the hypothesis half-way. To take a trivial illustration: just as a man who in a company of gentlemen made no advances, asked a warrant for every concession, and believed no one's word without proof, would cut himself off by such churlishness from all the social rewards that a more trusting spirit would earn,--so here, one who should shut himself up in snarling logicality and try to make the gods extort his recognition willy-nilly, or not get it at all, might cut himself off forever from his only opportunity of making the gods' acquaintance. This feeling, forced on us we know not whence, that by obstinately believing that there are gods (although not to do so would be so easy both for our logic and our life) we are doing the universe the deepest service we can, seems part of the living essence of the religious hypothesis. If the hypothesis were true in all its parts, including this one, then pure intellectualism, with its veto on our making willing advances, would be an absurdity; and some participation of our sympathetic nature would be logically required.

For Christians, God is personal, so knowing Him is in some ways like knowing another person. To know other people, you have to let them in first. So it doesn’t make sense to say ‘wait to believe until you have enough evidence that god exists’ because the evidence comes AFTER believing in him.

Conclusion

| James ends his speech with a beautiful call to courageous belief, but also to intellectual humility and tolerance. |

I, therefore, for one, cannot see my way to accepting the agnostic rules for truth-seeking, or willfully agree to keep my willing nature out of the game. I cannot do so for this plain reason, that a rule of thinking which would absolutely prevent me from acknowledging certain kinds of truth if those kinds of truth were really there, would be an irrational rule. That for me is the long and short of the formal logic of the situation, no matter what the kinds of truth might materially be.

I confess I do not see how this logic can be escaped. Were we scholastic absolutists, there might be more excuse. If we had an infallible intellect with its objective certitudes, we might feel ourselves disloyal to such a perfect organ of knowledge in not trusting to it exclusively, in not waiting for its releasing word. But if we are empiricists, if we believe that no bell in us tolls to let us know for certain when truth is in our grasp, then it seems a piece of idle fantasticality to preach so solemnly our duty of waiting for the bell. Indeed we may wait if we will—I hope you do not think that I am denying that—but if we do so, we do so at our peril as much as if we believed. In either case we act, taking our life in our hands. No one of us ought to issue vetoes to the other, nor should we bandy words of abuse. We ought, on the contrary, delicately and profoundly to respect one another's mental freedom: then only shall we bring about the intellectual republic; then only shall we have that spirit of inner tolerance without which all our outer tolerance is soulless, and which is empiricism's glory; then only shall we live and let live, in speculative as well as in practical things.

I began by a reference to Fitz James Stephen; let me end by a quotation from him. "What do you think of yourself? What do you think of the world? These are questions with which all must deal as it seems good to them. They are riddles of the Sphinx, and in some way or other we must deal with them. In all important transactions of life we have to take a leap in the dark. If we decide to leave the riddles unanswered, that is a choice; if we waver in our answer, that, too, is a choice: but whatever choice we make, we make it at our peril. If a man chooses to turn his back altogether on God and the future, no one can prevent him; no one can show beyond reasonable doubt that he is mistaken. If a man thinks otherwise and acts as he thinks, I do not see that any one can prove that he is mistaken. Each must act as he thinks best; and if he is wrong, so much the worse for him. We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take the wrong road we shall be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do? 'Be strong and of a good courage.' Act for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes. If death ends all, we cannot meet death better."

Objections

Consequences for Others

| James is an interesting counterpoint to philosophers advocating more skeptical approaches to rational belief (like Socrates, Clifford, and Descartes). Yet, he still loves the truth and believes it is important to living a good life. In fact, some could say James loves the truth even more than the skeptics because he is willing to leap towards the potential of truth even if it means being wrong sometimes. This approach is courageous and beautiful in some ways, but it opens the door to several negative consequences that James may not take seriously enough. |

Leaps Have Consequences for OthersThe first is the effect your leaps of faith may have on other people. Remember the ship owner from Clifford’s argument? That guy had a choice that was live, forced, and momentous, and his decision to leap resulted in all the crew and passengers dying. Or what if you’re considering leaping into a religion, but the beliefs of that religion entail the subjugation of women or persecution of non-believers? What if you decided to jump off that cliff, but the water wasn’t deep enough and now your loved ones have to live without you? Faith may lead to access to hidden truths and collective actions for the good of all that skeptics could never achieve, but it also can lead to undue suffering for innocent people impacted by your choices. It seems like one ought to weigh the potential negative effects on others of a false leap when deciding, not just what you might be missing out on. |

Gullibility

| The second potential drawback of allowing yourself to be guided partially by passions rather than purely by evidence is that you open the door to being duped. One who does not always critically question, and does not suspend judgment until sufficient evidence is obtained, is prone to fall into rabbit holes that they want to be true but are potentially foolish or even self-destructive. Conspiracy theorists and cults prey on people like this. |

Passion in Decision-Making

|

In putting forth a non-evidentialist theory of truth and decision-making, James defends the claim that passions always play a role in our decisions, and that this is a necessary part, not a bug, in the system. He writes: "Our non-intellectual nature does influence our convictions: pure insight and logic, whatever they might do ideally, are not the only things that really do produce our creeds." And further: “Our next duty, having recognized this mixed-up state of affairs, is to ask whether it be simply reprehensible and pathological, or whether, on the contrary, we must treat it as a normal element in making up our minds. The thesis I defend is, briefly stated, this: our passional nature not only lawfully may, but must, decide an option between propositions, whenever it is a genuine option that cannot by its nature be decided on intellectual grounds; for to say, under such circumstances, "Do not decide, but leave the question open," is itself a passional decision, - just like deciding yes or no, - and is attended with the same risk of losing the truth." James is arguing that passions should guide our decisions when reason fails to provide a clear answer. Indeed, he says this is unavoidable—even the Clifford’s of the world who suspend judgment are following a passion: the fear of being wrong. Do you agree that skepticism is driven by fear and not pure reason? Is emotion always a hindrance to sound decision-making, or is it sometimes necessary in order to leap towards important truths? Click onto the next tab for a real-world example of this question with deadly stakes. For more information on emotion in decision-making, watch this:

|

Example: Drone Pilots

The history of military technology can be described as a history of putting increasing distance between soldiers and the people they are killing. From warhammers, to swords, to spears, to guns, to artillery, to planes. Now, many of our military strikes come via drone, piloted by people who aren’t even in the same country as the targets, watching the results of their actions on a screen. One reason why the military has so enthusiastically embraced the use of RPAs is because it allows soldiers to bypass the very natural aversion to killing in direct combat. Through this distance, one would think the pilots are able to make better decisions both morally and strategically. By detaching yourself from the urgency and danger of direct combat, soldiers are able to calmy calculate about life-and-death decisions. And yet... Although these pilots face no imminent physical danger, a significant percentage of these remote pilots show symptoms that mirror PTSD, a disorder previously thought to only be linked with life-threatening experiences. For researchers like Brett Litz, the most appropriate way of categorizing these reactions is as "moral injuries": the "lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations [about oneself or the world]." So is this distance allowing us to remove messy biases and think logically, or is it actually creating more distortion in the part of our psychology designed (biologically and socially) to be our moral positioning system? What if the messiness of moral reasoning is a feature and not a bug; that simple calculations based on totalizing principles are actually less likely to lead us to do what we come to view as the right thing? If this is right, then the effects of creating distance between a soldier and their target may be debilitating to the soldier and add bias, the kind of bias that comes from forcing a decision maker to ignore relevant details.

Portions of this case study come from the book The Good Life Method by Notre Dame professors Paul Blaschko and Meghan Sullivan. |

Acknowledgements

This digital essay was prepared by Paul Blaschko and Sam Kennedy from the University of Notre Dame.

Cover Image Credit: Marta Cuesta, pixabay

Blaschko, Paul and Sam Kennedy. 2022. "James' The Will to Believe: Take a Leap of Faith." The Notre Dame Philosophy Commons