Is There A God?

Introduction

|

Natural theology is an approach to investigating religious questions through philosophical reasoning and observation of the natural world, without relying on specific religious doctrines or sacred texts. In this way, natural theologians have sought to provide a rational foundation for belief in a divine being or beings, and to draw conclusions about the features a divine being must have. However, since most religious traditions hold that God is transcendent—beyond the ability of any finite being like you or me to fully understand or describe in language—natural theology is often seen as only a preliminary way of knowing religious truths, which can then be further clarified or complemented by religious revelation from sacred texts, prophets, or spiritual experiences. In this interactive essay we'll look at arguments from two of the greatest natural theologians in the Christian tradition: Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109 AD) and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 AD). |

Anselm’s Ontological Argument

About Anselm

|

Our first example of natural theology comes from the 11th-century Christian theologian and philosopher Anselm of Canterbury, most famous for developing the ontological argument for the existence of God. In philosophy, "ontology" is the study of being: what types of entities exist, and how these types are related to each other. For example, an ontologist might investigate whether numbers exist and, if they do, how they relate to other things like human concepts, sets, and material objects. The basic idea behind Anselm's ontological argument is that God's existence can be proven simply by reflecting on what kind of thing God is. Anselm presented this argument in a work known as the Proslogion (originally titled Faith Seeking Understanding—the perfect mission statement for natural theology), written as a prayerful, contemplative discourse on God's nature. In the passage we will look at, he argues that even a "Foole" (atheist) must concede that God exists, since God's existence can be proven simply by reflecting on the definition or concept of God which is accepted by believers and nonbelievers alike. |

The Text

Truly there is a God, although the foole hath said in his heart, There is no God.

And so, Lord, do thou, who dost give understanding to faith, give me, so far as thou knowest it to be profitable, to understand that thou art as we believe; and that thou art that which we believe. And indeed, we believe that thou art a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. Or is there no such nature, since the foole hath said in his heart, there is no God? (Psalms xiv. 1). But, at any rate, this very foole, when he hears of this being of which I speak—a being than which nothing greater can be conceived—understands what he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding; although he does not understand it to exist.

For, it is one thing for an object to be in the understanding, and another to understand that the object exists. When a painter first conceives of what he will afterwards perform, he has it in his understanding, but he does not yet understand it to be, because he has not yet performed it. But after he has made the painting, he both has it in his understanding, and he understands that it exists, because he has made it.

Hence, even the foole is convinced that something exists in the understanding, at least, than which nothing greater can be conceived. For, when he hears of this, he understands it. And whatever is understood, exists in the understanding. And assuredly that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For, suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater.

Therefore, if that, than which nothing greater can be conceived, exists in the understanding alone, the very being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality.

Reality vs. Understanding

|

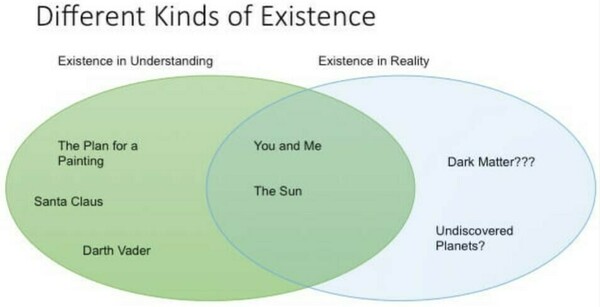

Anselm makes an important distinction between objects that exist in the understanding (the things we have ideas about) and objects that exist in reality. Some objects (like you and me) exist in both. Some objects are purely imaginary: they exist in the understanding but not in reality. And some objects exist in reality but not in the understading: they are unknown, and perhaps completely unknowable.

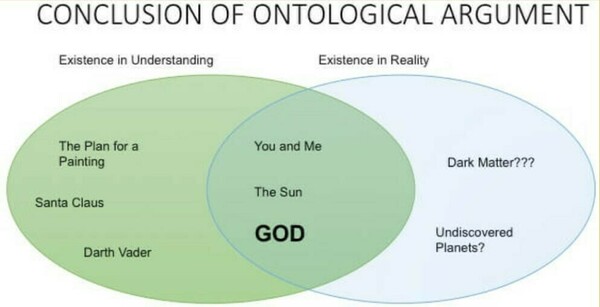

Anselm says the Foole mistakenly classifies God as an object that exists only in the understanding (in the green circle). He believes he can prove that God exists in both understanding and reality by definition.

|

The Ontological Argument Explained

|

With this distinction, we can now outline Anselm's argument. There are many formulations of the ontological argument (and historians of philosophy dispute exactly how it works). Here is one simple reconstruction.

Anselm assumes that even an atheist will agree that such a thing exists in the understanding, meaning one can understand the idea of a perfect being. Perfection is one of the divine attributes. Divine attributes play a crucial role in natural theology, both in investigations of how a certain attribute is to be understood and in arguments for God's existence, which often proceed by trying to establish that something must have this or that divine attribute. The success of the ontological argument will depend on how we understand the attribute of perfection and the idea of the greatest conceivable being.

If you had a choice between merely imagining something you really want (a brand new sports car, for example) and actually having it, which would you prefer? The thing in reality, Anselm says, is obviously greater than the thing only in understanding. (C) God must exist in reality. Given that ‘God’ is the greatest possible thing, it can’t only exist in understanding, since existing in reality would be greater. So as soon as you admit that God exists in your imagination, it logically must exist in reality. |

Guanilo's Objection: The Perfect Island

|

As soon as Anselm offered his argument it drew objections. Guanilo, another monk, argued that Anselm's argument must be flawed, because otherwise the same kind of argument could also be used to prove the existence in reality of some truly crazy entities. Here is Guanio's "Reply on Behalf of the Fool": |

They say that there is the ocean somewhere an island which, because of the difficulty (or rather the impossibility) of finding that which does not exist, some have called the ‘Lost Island.’ And the story goes that it is blessed with all manner of priceless riches and delights in abundance and is superior everywhere in abundance to all those other lands that men inhabit. Now, if anyone tell me that it is like this, I shall easily understand what is said, since nothing is difficult about it. But if he should then go on to say, as though it were a logical consequence of this: You cannot any more doubt that this island that is more excellent than all other lands truly exists somewhere in reality than you can doubt that it is in your mind; and since it is more excellent to exist not only in the mind alone but also in reality, therefore it must needs be that it exists. For if it did not exist, any other land existing in reality would be more excellent than it, and so this island, already conceived by you to be more excellent than others, will not be more excellent. If, I say, someone wishes thus to persuade me that this island really exists beyond all doubt, I should either think that he was joking, or I should find it hard to decide which of us I ought to judge the bigger fool – I, if I agreed with him, or he, if he thought that he had proved the existence of this island.

Guanilo's Argument ExplainedGuanilo is offering a parody of Anselm's argument, exactly identical except that premise 2 deals with "The Lost Island" instead of with God. The point is to convince us to reject either Anselm's reasoning or the assumptions he makes about perfection as an attribute.

(C) The Lost Island must exist in reality. Does this parody gives us reason to question Anselm's argument? If so, where does the ontological argument for God's existence go wrong? Is it not even possible for a "perfect" thing to "exist" in our understanding? Should we think that existence in reality does not make something "greater"? |

The Five Ways (Arguments) of Aquinas

|

Thomas Aquinas took a different approach to arguing for God's existence. He focuses on the need for there to be some entity responsible for all of the change we observe in the world – an "unmoved mover" at the foundation of everything in reality. This is known as the cosmological argument for the existence of God. Aquinas has a unique style of writing that requires some introduction. Here is Notre Dame President John Jenkins (also an Aquinas scholar) talking about how to read Aquinas. |

Way 1: Change

The Text

It is certain, and evident to our senses, that in the world some things are in motion. Now whatever is in motion is put in motion by another, for nothing can be in motion except it is in potentiality to that towards which it is in motion; whereas a thing moves inasmuch as it is in act. For motion is nothing else than the reduction of something from potentiality to actuality. But nothing can be reduced from potentiality to actuality, except by something in a state of actuality.

Thus that which is actually hot, as fire, makes wood, which is potentially hot, to be actually hot, and thereby moves and changes it.

Now it is not possible that the same thing should be at once in actuality and potentiality in the same respect, but only in different respects. For what is actually hot cannot simultaneously be potentially hot; but it is simultaneously potentially cold. It is therefore impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Therefore, whatever is in motion must be put in motion by another. If that by which it is put in motion be itself put in motion, then this also must needs be put in motion by another, and that by another again. But this cannot go on to infinity, because then there would be no first mover, and, consequently, no other mover; seeing that subsequent movers move only inasmuch as they are put in motion by the first mover; as the staff moves only because it is put in motion by the hand. Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God.

| Note: Motion for Aquinas is not just physical movement, it is change from potentiality to actuality, from it being possible for something to happen to it actually happening. |

Broken Down

A thing can’t be in motion and not in motion at the same time in the same way. For example, I’m not in motion right now in the sense that I am seated, but I am in motion in the sense that my fingers are moving as they type. So I’m in motion and not at the same time, but not in the same sense of ‘motion.’ Conclusion 1: Therefore, it is impossible that in the same respect and in the same way a thing should be both mover and moved, i.e. that it should move itself. Only things in motion can put things in motion. So if a thing at rest put itself into motion, then it would have to already have been in motion, which is a contradiction.

This follows from Conclusion 1.

Imagine a chain of dominoes. If I asked why the last domino moved, you would say because the domino before it hit it. Then I ask why that domino moved, and you say because it was hit by the one before it. And so on and so on.

There can’t be an infinite chain of things in motion moving other things in motion, because what put the whole thing in motion in the first place? Conclusion 2: Therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other, and this everyone understands to be God. |

Way 2: Causation

The Text

The second way is from the nature of the efficient cause. In the world of sense we find there is an order of efficient causes.

There is no case known (neither is it, indeed, possible) in which a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself; for so it would be prior to itself, which is impossible. Now in efficient causes it is not possible to go on to infinity, because in all efficient causes following in order, the first is the cause of the intermediate cause, and the intermediate is the cause of the ultimate cause, whether the intermediate cause be several, or only one. Now to take away the cause is to take away the effect. Therefore, if there be no first cause among efficient causes, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. But if in efficient causes it is possible to go on to infinity, there will be no first efficient cause, neither will there be an ultimate effect, nor any intermediate efficient causes; all of which is plainly false. Therefore it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause, to which everyone gives the name of God.

| Note: Think of causation here in a broad sense. It refers to any causes that bring about effects in the world. For example, parents are the joint cause of their children. The cause of a sculpture is the artist who created it. |

Broken Down

Causes always happen in time order, cause coming before effect. So nothing can cause itself to happen because that would mean it existed prior to existing. Think of a human giving birth to itself.

If a cause doesn’t happen, the effects won’t happen either. Conclusion 1: Therefore, if there is no first cause, there will be no ultimate, nor any intermediate cause. If we don’t concede that there was a first cause, then there would be no chain of causes after it.

There can be an infinite chain of causes, there must be one first uncaused cause in order for the chain to exist at all. Similar to the first argument. Conclusion 2: Therefore it is necessary to admit a first cause, to which everyone gives the name of God. |

Way 3: Contingency

The Text

We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found to be generated, and to corrupt, and consequently, they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence — which is absurd. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which is necessary. But every necessary thing either has its necessity caused by another, or not. Now it is impossible to go on to infinity in necessary things which have their necessity caused by another, as has been already proved in regard to efficient causes. Therefore we cannot but postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God.

Broken Down

All things have a beginning and an end. They come into existence, decay, and pass out of existence. Therefore, all things could not exist at any point. We call this contingency – all beings in our universe are contingent.

Since all things are contingent, none of them have always existed. All things that have an end must also have a beginning.

Calling back to the causality argument, things always are brought into existence from other things that already exist. So if at any point the universe went to zero – nothing at all existed –it would stay at zero forever, because nothing can come from nothing.

Nothing can come from nothing, and no beings can have always existed, but it’s obvious that things do exist. Therefore, there must be something necessary that exists, something of which it is impossible that it should not exist, that created the chain of being.

See Causation argument. Conclusion: Therefore we must postulate the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God. |

Divine Attributes in Aquinas' Third Way

|

By this third way, Aquinas has focused his attention on two divine attributes that are important to his argument.

|

Way 4: Degree

The Text

The fourth way is taken from the gradation to be found in things. Among beings there are some more and some less good, true, noble and the like. But "more" and "less" are predicated of different things, according as they resemble in their different ways something which is the maximum, as a thing is said to be hotter according as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest; so that there is something which is truest, something best, something noblest and, consequently, something which is uttermost being; for those things that are greatest in truth are greatest in being. Now the maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus; as fire, which is the maximum heat, is the cause of all hot things. Therefore there must also be something which is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection; and this we call God.

Broken Down

Many philosophers have challenged this assumption. Why should it be the case that just because there is lesser and greater there is a maximum. Hold up your hand – it’s clear (probably) that your middle finger is longer than your pinky finger, without reference to some maximally big finger. We don’t need a maximum to measure, we just need a tool of measurement.

To illustrate this premise, Aquinas gives the example of fire, which is both the hottest thing, and the cause of heat in all other hot things. But does it always work this way? Aquinas may be drawing on Plato's theory of Forms, according to which the Form of Beauty (for example) is both perfectly beautiful and the cause of beauty in all beautiful things (which are beautiful because they "participate in" this Form). But without this kind of theoretical framework, this premise also seems open to challenge. Can you think of any potential counterexamples to it? Conclusion: There exists a maximally perfect being in every way, whom we call God. The greatest of all beings must be the greatest of all qualities of beings, like wisdom, beauty, goodness, etc. |

| Notice that this conclusion is stronger than the previous three. Before, Aquinas had only proved that there was something that was an uncaused cause, unmoved mover, and necessary being. Now, Aquinas seems to have proven divine attributes related to this beings character: That it is maximally wise, maximally beautiful, maximally everything. |

Way 5: Design

The Text

The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world. We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.

Broken Down

|

This might be Aquinas’ most famous argument: Design implies designer. This argument was strongly influenced by Aristotle, whom Aquinas held in such high regard that he referred to him simply as “the Philosopher,” as if he was the only one worthy of the title.

This idea is also central to Aristotle's "function argument" in the Nicomachean Ethics.

This might be seen as an objection to Aristotle’s original argument for Premise 1, that, contrary to Aristotle's view, natural objects have no purpose. But instead, Aquinas doubles down on Premise 1 by inferring that natural objects are in fact designed, as Premise 3 implies.

Conclusion: A designer of all things exists, and this we call God. |

Other Design Arguments

|

Aquinas’ Design Argument inspired many others. Watch this for a brief overview of some other formulations of the argument:

|

Objections to the Five Ways

| Aquinas considers and replies to objections to his argument at the end of the Five Ways. |

Objection 1: The Problem of Evil

It seems that God does not exist; because if one of two contraries be infinite, the other would be altogether destroyed. But the word "God" means that He is infinite goodness. If, therefore, God existed, there would be no evil discoverable; but there is evil in the world. Therefore God does not exist.

Aquinas’ Reply

As Augustine says (Enchiridion xi): "Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil." This is part of the infinite goodness of God, that He should allow evil to exist, and out of it produce good.

Objection 2: Occam’s Razor (the simplest explanation is best)

Further, it is superfluous to suppose that what can be accounted for by a few principles has been produced by many. But it seems that everything we see in the world can be accounted for by other principles, supposing God did not exist. For all natural things can be reduced to one principle which is nature; and all voluntary things can be reduced to one principle which is human reason, or will. Therefore there is no need to suppose God's existence.

Aquinas’ Reply (God explains more)

Since nature works for a determinate end under the direction of a higher agent, whatever is done by nature must needs be traced back to God, as to its first cause. So also whatever is done voluntarily must also be traced back to some higher cause other than human reason or will, since these can change or fail; for all things that are changeable and capable of defect must be traced back to an immovable and self necessary first principle.

Other Objections Not Considered

|

|

|

|

Summary and Next Steps

| As we've seen, the natural theological arguments tend to rely on premises about key divine attributes. Atheists can resist the arguments by denying that these attributes are coherent or possible (i.e. it is incoherent to imagine a perfect being). Or they can resist the logic of the arguments. A further question is whether theism could be rational even if there is no decisive argument proving God's existence or nature. This leads into a broader debate in philosophy of religion: what does rational faith require of us? |

Acknowledgements

This digital essay was prepared by Paul Blaschko and Meghan Sullivan from the University of Notre Dame, and edited by Justin Christy and Sam Kennedy.

Blaschko, Paul and Meghan Sullivan. 2022. "Natural Theology: Reason about God." The Notre Dame Philosophy Commons. Justin Christy and Sam Kennedy (eds.).