Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche

As I understand it, philosophy as a way of life (PWOL) aims to integrate our philosophical commitments into our ordinary lives. I take my cue from Pierre Hadot’s influential work on PWOL. According to Hadot, PWOL involves both philosophical reasoning and practical exercises to alter your attitudes and dispositions. The motivation for PWOL is that philosophy should matter: it should change and transform your existence. The ancient stoic Epictetus suggests this conception of philosophy when he says: “a carpenter does not come up to you and say ‘listen to me discourse about the art of carpentry’ but he makes a contract for a house and he builds it….Do the same thing for yourself.”[1] I tend to agree.

But how do you live a philosophical life? Hadot thinks that “spiritual exercises” are important. Spiritual exercises are practices that aim “to effect a modification and a transformation in the subject who practiced them.”[2] Spiritual exercises seek to alter your attitudes and behavior so that they’re in line with your philosophical commitments. Examples of spiritual exercises include negative and positive visualization, contemplating our lives from the perspective of the cosmos, subjecting negative patterns of thought to critique, gratitude exercises, meditation, and more.

But, if PWOL involves spiritual exercises, then it must be empirical and, thus, interdisciplinary in nature. Why’s that? Let’s assume for the moment that one aim of spiritual exercises is to change practitioners, to alter their attitudes and dispositions. Well, do we have any reason to believe that spiritual exercises have this effect? That’s an empirical question. We can’t answer this question just by thinking about it. History reveals that our theoretical speculations about the effects of different interventions can be radically off (Got pneumonia? Why not give bloodletting a try?). Instead, we need rigorous empirical methods to estimate the effects of spiritual exercises. So, philosophers who are interested in PWOL should consult with empirical researchers for insight into how these practices work and what they do.

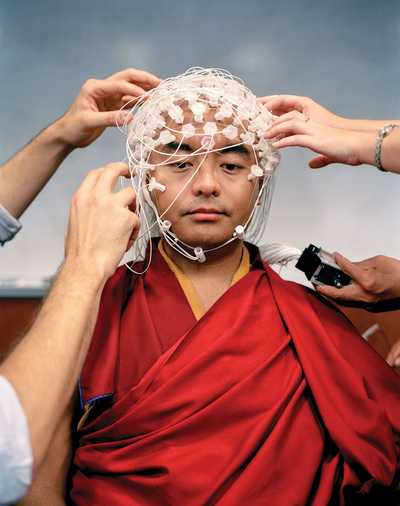

Here’s an illustration. Several philosophical traditions hold that one important spiritual exercise is meditation. Meditation is thought to have key benefits. Meditation sooths the mind and makes you more tranquil. If so, then meditation could be helpful in achieving what the Ancient Greeks called “ataraxia”--equanimity or peace of mind. The Buddhist tradition suggests that meditation can help us to internalize the truth of anatta, the view that selves don’t exist. The practice of mettā, or loving-kindness meditation, seeks to cultivate compassion for all living beings. But does meditation really generate these benefits? Again, we can’t answer this question without sustained empirical investigation. And the results of this investigation could be surprising.

Does this mean that PWOL just collapses into empirical psychology? Nope. PWOL has an ineliminable normative component. Philosophical reasoning and reflection is still necessary for evaluating the goal of spiritual exercises. What’s the good life like? Is ataraxia truly valuable in itself? Also, most conceptions of the good life involve an ethical component. I’m going to go out on a limb here and assert that living the good life requires that you behave in a morally decent way. But what does it take to be morally decent? Once again, philosophical reasoning and reflection are crucial to answering this question. So, both philosophical and empirical investigation is necessary to understand the content of the good life and path to achieving it.