How should people approach traditions?

Introduction

|

Joseph Henrich is a professor of human evolutionary biology. His research deals with the evolution of human culture and the emergence of complex human institutions. This interactive essay covers Chapter 7 of Henrich's The Secret of Our Success (2016). In this book, Henrich explores the role of culture and tradition in the evolutionary success of the human species. Using a variety of case studies, he argues that social learning, passed on through cultural traditions, has propelled us to our position as the most dominant species on Earth.  |

The Curious Case of Cassava

| Henrich begins this chapter by exploring the preparation of the staple crop manioc, or cassava, in order to introduce the concepts of causal opacity and cultural evolution. |

As one of the world’s staple crops, manioc (or cassava) is a highly productive, starch-rich tuber that has permitted relatively dense populations to inhabit drought-prone tropical environments. I’ve lived on it, both in Amazonia and in the South Pacific. It’s tasty and filling. However, depending on the variety of manioc and the local ecological conditions, the tubers can contain high levels of cyanogenic glucosides, which release toxic hydrogen cyanide when the plant is eaten. If eaten unprocessed, manioc can cause both acute and chronic cyanide poisoning. Chronic poisoning, because it emerges only gradually after years of consuming manioc that tastes fine, is particularly insidious and has been linked to neurological problems, developmental disorders, paralysis in the legs, thyroid problems (e.g., goiters), and immune suppression. These so-called "bitter” manioc varieties remain highly productive even in infertile soils and ecologically marginal environments, in part due to their cyanogenic defenses against insects and other pests.

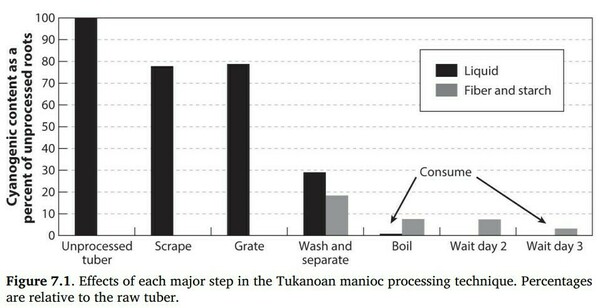

In the Americas, where manioc was first domesticated, societies who have relied on bitter varieties for thousands of years show no evidence of chronic cyanide poisoning. In the Colombian Amazon, for example, indigenous Tukanoans use a multistep, multiday processing technique that involves scraping, grating, and finally washing the roots in order to separate the fiber, starch, and liquid. Once separated, the liquid is boiled into a beverage, but the fiber and starch must then sit for two more days, when they can then be baked and eaten. Figure 7.1 shows the percentage of cyanogenic content in the liquid, fiber, and starch remaining through each major step in this processing.

Such processing techniques are crucial for living in many parts of Amazonia, where other crops are difficult to cultivate and often unproductive. However, despite their utility, one person would have a difficult time figuring out the detoxification technique. Consider the situation from the point of view of the children and adolescents who are learning the techniques. They would have rarely, if ever, seen anyone get cyanide poisoning, because the techniques work. And even if the processing was ineffective, such that cases of goiter (swollen necks) or neurological problems were common, it would still be hard to recognize the link between these chronic health issues and eating manioc. Most people would have eaten manioc for years with no apparent effects. Low cyanogenic varieties are typically boiled, but boiling alone is insufficient to prevent the chronic conditions for bitter varieties. Boiling does, however, remove or reduce the bitter taste and prevent the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting). So, if one did the common-sense thing and just boiled the high-cyanogenic manioc, everything would seem fine. Since the multistep task of processing manioc is long, arduous, and boring, sticking with it is certainly nonintuitive. Tukanoan women spend about a quarter of their day detoxifying manioc, so this is a costly technique in the short term.

Now consider what might result if a self-reliant Tukanoan mother decided to drop any seemingly unnecessary steps from the processing of her bitter manioc. She might critically examine the procedure handed down to her from earlier generations and conclude that the goal of the procedure is to remove the bitter taste. She might then experiment with alternative procedures by dropping some of the more labor-intensive or time-consuming steps. She’d find that with a shorter and much less labor-intensive process, she could remove the bitter taste. Adopting this easier protocol, she would have more time for other activities, like caring for her children. Of course, years or decades later her family would begin to develop the symptoms of chronic cyanide poisoning.

Thus, the unwillingness of this mother to take on faith the practices handed down to her from earlier generations would result in sickness and early death for members of her family. Individual learning does not pay here, and intuitions are misleading. The problem is that the steps in this procedure are causally opaque — an individual cannot readily infer their functions, interrelationships, or importance. The causal opacity of many cultural adaptations had a big impact on our psychology.

The point here is that cultural evolution is often much smarter than we are. Operating over generations as individuals unconsciously attend to and learn from more successful, prestigious, and healthier members of their communities, this evolutionary process generates cultural adaptations. Though these complex repertoires appear well designed to meet local challenges, they are not primarily the products of individuals applying causal models, rational thinking, or cost-benefit analyses. Often, most or all of the people skilled in deploying such adaptive practices do not understand how or why they work, or even that they “do” anything at all. Such complex adaptations can emerge precisely because natural selection has favored individuals who often place their faith in cultural inheritance—in the accumulated wisdom implicit in the practices and beliefs derived from their forbearers—over their own intuitions and personal experiences. In many crucial situations, intuitions and personal experiences can lead one astray.

Causal Opacity

If a tradition, or some part of a tradition, is causally opaque, it means the individuals doing it can't easily tell what purpose the tradition serves, or how one step in a ritual is related to the others.

Because the participants don't understand the function, they might be tempted by their intuition or reason to get rid of what seem like useless or meaningless steps in a process, or get rid of a traditional practice entirely. But doing so could be dangerous, Henrich says - just because we don't know the function doesn't mean there isn't one, and these cultural practices typically have the benefit of generations of experience and trial and error.

Objections: Cultural Evolution and Truth

|

Henrich's argument in favor of trusting tradition relies on his concept of "cultural evolution". Through this process, which operates similarly to biological evolution, cultural practices that aid in the health, survival, and reproduction of the community are passed down—but the rationale for the practice, or knowledge of how it functions, often is not. Individuals simply copy what successful ancestors have done, without really understanding why. This kind of trust in traditions may promote survival, but what is the relationship between cultural evolution and truth? Philosophers might raise at least two concerns with Henrich's argument: |

1. Survival Isn't SuperiorityIn evolutionary biology, organisms that survive long enough to reproduce have their genes passed on to the next generation (they 'win'). An organism 'wins' because (a) they had particular mutations that made them better adapted to winning than others, (b) they didn't have any mutations that were so big of a hindrance to them that they couldn't win, and/or (c) they got lucky. Over a long long time, (c) becomes less of a factor, so good traits from (a) persist and bad traits from (b) die out. But surviving organisms aren't necessarily "superior" to dead ones in any sense other than survival. The goal of the organisms is always the same (survive and reproduce), so new, more complex adaptations aren't "better" unless they squeeze out the older adaptations. In evolutionary terms, a species of coral that hasn't changed for millions of years is equally as good as a human that gives birth - they both survived.

What this means for cultural evolution is that, while it may select for traditions that lead to our survival and reproduction, it doesn't necessarily select for traditions that are better in any of the other ways we care about—for example, those that are more moral, more truthful, more pleasurable, or more efficient. |

2. Traditions as 'Dead Dogmas'John Stuart Mill held that a person who practices a tradition without knowing why is in possession of "a dead dogma, not a living truth". Mill argues that, as rational beings, we should always seek an understanding of the reasons behind our beliefs and our practices. The alternative is an ignorance that can be dangerous, and perhaps even inhuman. |

This claim is one of the ones that got Darwin into the biggest trouble, and one for which we owe him the most thanks. From Aristotle on through the Medieval Period, people thought of life in terms of what's called the "Great Chain of Being." According to this idea, all living things exist on a hierarchy from least to greatest, starting from lowly plants and typically culminating in humans, then angels, then God as the greatest being. Darwin's theory of natural selection through that whole chain out the window by saying that evolution is directionless - things adapt and survive, but they don't get "better" with each bit of added complexity. Humans, therefore, are biologically no better than any other surviving species... You can imagine why this got the Church Fathers all hot and bothered.

It's Better Not To Know

|

Some traditional practices can be properly executed only if those who do so have an understanding of why the practice is done. For example, many religions commemorate the onset of adulthood with rituals such as confirmation in Catholicism or a bar/bat mitzvah in Judaism. Such customs rely on an understanding of the implications of one’s commitment to one’s faith; otherwise, they lose their significance. If Seth doesn’t know that having a bar mitzvah confirms his Jewish identity and commitment to be involved in the Jewish community, then the event no longer has meaning. But, as Henrich argues below, there are also cases where knowing the reasons behind a tradition is counterproductive. To illustrate this point, Henrich points to the Naskapi' use of ritual divination to guide their hunting, not realizing that the practice's efficacy rests on its function as a randomizer. |

As I noted, much work in psychology shows that people (well, at least educated Westerners) are subject to the Gambler’s Fallacy, in which we perceive streaks in the world where none exist or we believe that we are “due” after an extended losing streak. In fact, we struggle to recognize a sequence of hits and misses as random — instead, we find phony patterns in the randomness. One famous version of this is the hot-hand fallacy in basketball, in which people perceive a player as suddenly better than his long-term scoring average would suggest (it’s an illusion). This is a problem for us, since the best strategies in life sometimes require randomizing. We are just not good at shutting down our mental pattern recognizers.

When hunting caribou, Naskapi foragers in Labrador, Canada, had to decide where to go. Common sense might lead one to go where one had success before or to where friends or neighbors recently spotted caribou. That is, hunters want to match the locations of caribou while caribou want to mismatch the hunters, to avoid being shot and eaten. If a hunter shows any bias to return to previous spots, where he or others have seen caribou, then the caribou can benefit (survive better) by avoiding those locations (where they have previously seen humans). Thus, the best hunting strategy requires randomizing. Can cultural evolution compensate for our cognitive inadequacies?

Traditionally, Naskapi hunters decided where to go to hunt using divination and believed that the shoulder bones of caribou could point the way to success. To start the ritual, the shoulder blade was heated over hot coals in a way that caused patterns of cracks and burnt spots to form. This patterning was then read as a kind of map, which was held in a prespecified orientation. The cracking patterns were (probably) essentially random from the point of view of hunting locations, since the outcomes depended on myriad details about the bone, fire, ambient temperature, and heating process. Thus, these divination rituals may have provided a crude randomizing device that helped hunters avoid their own decision-making biases. The undergraduates in the Matching Pennies game could have used a randomizing device like divination, though the chimps seem fine without it.

This example makes a key point: not only do people often not understand what their cultural practices are doing, but sometimes it may even be important that they don’t understand what their practices are doing or how they work. If people came to understand that bone divination didn’t actually predict the future, the practice would probably be dropped or people would increasingly ignore ritual findings in favor of their own intuitions.

Man is a Cultural Animal

| In this passage, Henrich argues that humans are cultural animals. We tend to copy each other when we see someone achieve our desired result, even when copying goes against our instincts or our judgment. This is a process psychologists call over-imitation. |

Crucial to making cultural adaptations like manioc, corn, or nardoo processing work is not only faithfully copying all the steps, but also sometimes actually avoiding putting much emphasis on causal understandings that one might build on the fly, on one’s own. As shown above, dropping seemingly unnecessary steps from one’s cultural repertoire can result in neurological disorders, paralysis, pellagra, reduced hunting success, pregnancy problems, and death. In a species with cumulative cultural evolution, but only in such a species, faith in one’s cultural inheritance often favors greater survival and reproduction.

Dovetailing with the above field observations, experimental work with children and adults on the fidelity of cultural learning allows us to put a microscope on the cultural transmission process. Recently, psychologists have studied the when and why of people’s willingness to copy the seemingly irrelevant steps used by another to get to a reward. In a typical experiment, a participant sees a model engage in a multistep procedure that involves using simple tools to push, pull, lift, poke, and tap an “artificial fruit” (often a large box with doors and holes). The procedure usually results in obtaining some desirable outcome, such as a toy or snack. Some of the steps in the procedure are not apparently required to achieve the goal of getting the reward. Sometimes people even copy steps with no evident material-physical connection to the outcome. Notorious for inappropriately naming of behavioral patterns, psychologists have labelled this not-particularly-shocking phenomenon overimitation.

The robust results from these kinds of experiments are that children and adults are rather inclined to copy whatever the model does to obtain the reward. People even copy the irrelevant actions when they are alone, after they think the experiment is over, and when they’ve been told explicitly not to copy any irrelevant actions. However… people are more likely to copy irrelevant actions when the model is older and higher in prestige. This is also not merely some tendency of little children: assuming the problem is sufficiently opaque, the magnitude of “overimitation” increases with age. This also isn’t just educated Western peoples. Research in the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa, whose populations lived as foragers until recent decades, show them to be at least as inclined to high-fidelity cultural transmission as Western undergraduates.

Our reliance on cultural transmission, however, goes much deeper. In addition to acquiring practices and beliefs, which may violate our intuitive understandings, we can also acquire tastes, preferences, and motivations. These too can be acquired in the face of our instinctual or innate inclinations. Such acquisitions do not mean we lack instincts or innate inclinations, but merely that natural selection has endowed our cultural learning systems with the ability to, under the right conditions, overwrite or work around them.

Overcoming Instinct: Why Chili Peppers Taste Good

|

Some traditions involve activities that seem unsafe. For example, bullfighting poses a significant risk of harm to those involved. Regardless of potential danger, though, such traditions are still widely practiced. Henrich argues that although some activities are counterintuitive from the perspective of evolutionary biology, our cultural adaptations supersede our inclination to avoid dangerous activity. Our desire to engage in these traditions is rooted in a reinterpretation of their danger, viewing it as positive, not negative. But Henrich also suggests that some cultural adaptations are evolutionarily beneficial as well. As you read this excerpt, consider Henrich’s rationale for why we engage in dangerous activity. Do you think his argument is convincing? |

Why do we use spices in our foods? In thinking about this question keep in mind that (1) other animals don’t spice their foods, (2) most spices contribute little or no nutrition to our diets, and (3) the active ingredients in many spices are actually aversive chemicals that evolved to keep insects, fungi, bacteria, mammals, and other unwanted critters away from the plants that produce them.

Several lines of evidence indicate that spicing may represent a class of cultural adaptations to the problem of food-borne pathogens. Many spices are antimicrobials that can kill pathogens in foods. Globally, the common spices are onions, pepper, garlic, cilantro, chili peppers (capsicum), and bay leaves. Here’s the idea: the use of many spices represents a cultural adaptation to the problem of pathogens in food, especially in meat. This challenge would have been most important before refrigerators came on the scene. To examine this, two biologists, Jennifer Billing and Paul Sherman, collected 4,578 recipes from traditional cookbooks from populations around the world. They found three distinct patterns.

- Spices are, in fact, antimicrobial. The most common spices in the world are also the most effective against bacteria. Some spices are also fungicides. Combinations of spices have synergistic effects, which may explain why ingredients like chili powder (a mix of red pepper, onion, paprika, garlic, cumin and oregano) are so important. And ingredients like lemon and lime, which are not on their own potent antimicrobials, appear to catalyze the bacteriakilling effects of other spices.

- People in hotter climates use more spices, and more of the most effective bacteria killers. In India and Indonesia, for example, most recipes used many antimicrobial spices, including onions, garlic, capsicum, and coriander. Meanwhile, in Norway, recipes use some black pepper and occasionally a bit of parsley or lemon, but that’s about it.

- Recipes appear to use spices in ways that increase their effectiveness. Some spices, like onions and garlic, whose killing power is resistant to heating, are deployed in the cooking process. Other spices, like cilantro, whose antimicrobial properties might be damaged by heating are added fresh in recipes.

Thus, many recipes and preferences appear to be cultural adaptations that are suited to local environments and that operate in subtle and nuanced ways not understood by those of us who love spicy foods. Billing and Sherman speculated that these evolved culturally, as healthier, more fertile, and more successful families were preferentially imitated by less successful ones. This is quite plausible given what we know about our species’ evolved psychology for cultural learning, including specifically cultural learning about foods and plants.

Among spices, chili peppers are an ideal case. Chili peppers were the primary spice of New World cuisines prior to the arrival of Europeans and are now routinely consumed by about a quarter of all adults globally. Chili peppers have evolved chemical defenses, based on capsaicin, that make them aversive to mammals and rodents but desirable to birds. In mammals, capsicum directly activates a pain channel (TrpV1), which creates a burning sensation in response to various specific stimuli, including acid, high temperatures, and allyl isothiocyanate (which is found in mustard and wasabi). These chemical weapons aid chili pepper plants in their survival and reproduction, because birds provide a better dispersal system for the plants’ seeds than other options (like mammals). Consequently, chilies are innately aversive to nonhuman primates, babies, and many human adults. Capsaicin is so innately repellent that nursing mothers are advised to avoid chili peppers lest their infants reject their breast milk, and in some societies, capsicum is even put on a mother’s breasts to initiate weaning. Yet adults who live in hot climates regularly incorporate chilies into their recipes. And those who grow up among people who enjoy eating chili peppers not only eat chilies but love eating them. How do we come to like the experience of burning and sweating—the activation of pain channel TrpV1?

Research by the psychologist Paul Rozin shows that people come to enjoy the experience of eating chili peppers mostly by reinterpreting the pain signals caused by capsicum as pleasure or excitement. Based on work in the highlands of Mexico, children acquire this preference gradually, without being pressured or compelled. They want to learn to like chili peppers, to be like those they admire. This fits with what we’ve already seen: children readily acquire food preferences from older peers. The bottom line is that culture can overpower our innate mammalian aversions when necessary and without us knowing it.

Summary

Summary Text

|

Henrich concludes by noting that although we may be able to uncover the roots of particular cultural traditions, that information is useless if we don't also recognize the broader structures those practices derive from. To truly appreciate the role of cultural traditions in humanity’s evolutionary journey, we must understand the complex societal structures that gave rise to these traditions. |

As a product of this long-running duet between cumulative cultural evolution and genes, our brains have genetically adapted to a world in which information crucial to our survival was embedded implicitly in a vast body of knowledge that we inherit culturally from previous generations. This information comes buried in daily cooking routines (manioc), taboos, divination rituals, local tastes (chili peppers), mental models, and tool-manufacturing scripts (arrow shafts). These practices and beliefs are often (implicitly) MUCH smarter than we are, as neither individuals nor groups could figure them out in one lifetime. For these evolutionary reasons, learners first decide if they will “turn on” their causal-model builders at all, and if so, they have to carefully assess how much mental effort to put into them. And if cultural transmission supplies a prebuilt mental model for how things work, learners readily acquire and adhere to those.

Of course, people can, and do, attempt to break down complex procedures and protocols in order to understand the causal links between them and to engineer better versions. They also alter practices through experimentation, errors in learning, and idiosyncratic actions. Nevertheless, as a cultural species, we have an instinct to faithfully copy complex procedures, practices, beliefs, and motivations, including steps that may appear causally irrelevant, because cultural evolution has proved itself capable of constructing intricate and subtle cultural packages that are far better than we could individually construct in one lifetime. Often, people don’t even know what their practices are actually doing, or that they are “doing” anything. Spicy-food lovers in hot climates don’t know that using recipes involving garlic and chili peppers protect their families from meat-borne pathogens. They just culturally inherited the tastes and the recipes, and implicitly had faith in the wisdom accumulated by earlier generations.

Finally, we humans do, of course, construct causal models of how the world works. However, what’s often missed is that the construction of these models has long been sparked and fostered by the existence of complex culturally evolved products. When people have accurately speculated on why they do something, this realization often occurs after the fact: “Why do we always do it this way? There must be a reason.… Maybe it’s because…” However, just because some people have speculated accurately as why they themselves, or their groups, do something in a particular way does not mean that this is the reason why they do it. An enormous amount of scientific causal understanding, for example, has developed in trying to explain existing technologies, like the steam engine, hot air balloon, or airplane. A device or technology often preexisted the development of any causal understanding, but by existing, such cultural products opened a window on the world that facilitated the development of an improved causal understanding. That is, for much of human history until recently, cumulative cultural evolution drove the emergence of deeper causal understandings much more than causal understanding drove cultural evolution.

Summary Video

Acknowledgements

This digital essay was prepared by Sam Kennedy, Blake Ziegler, and Justin Christy from the University of Notre Dame.

Kennedy, Sam and Blake Ziegler. 2022. "Henrich’s The Secret of our Success: Trust Tradition." The Notre Dame Philosophy Commons